The B2B sharing revolution

Since the 2008 crisis, we have seen the consumer-to-consumer sharing economy (C2C sharing) take off, whose leaders are now known to all: Uber, Airbnb, etc. Another sharing economy is possible and even extraordinarily promising: business-to-business sharing, or B2B sharing.

This new economy surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the emergencies that all actors had to face, especially businesses, driving them to share resources and co-create value. The collaborative practices learned in this ordeal should be sustained and can be scaled up in the future. B2B sharing, potentially worth trillions of dollars, could reinvent entire sectors.

B2B sharing incentivizes businesses to unlearn their basic instincts to hoard resources and compete ruthlessly—the hallmark of capitalist economies—and enables companies to cooperate and succeed in our interdependent world. B2B sharing can also greatly benefit societies that know how to accelerate its growth and use it wisely to support their ecological transition.

Known for his seminal work on frugal innovation, Navi Radjou offers here a panoramic vision of this emerging B2B sharing economy by inscribing its different dimensions in a taxonomy and a “maturity model” (roadmap) that allows each company to benchmark itself and to envisage new development possibilities. This empirical approach is accompanied by a host of inspiring experiences in Europe, North America, and Asia, at the international level as well as at the sub-national level (in the cities, territories, regions…).

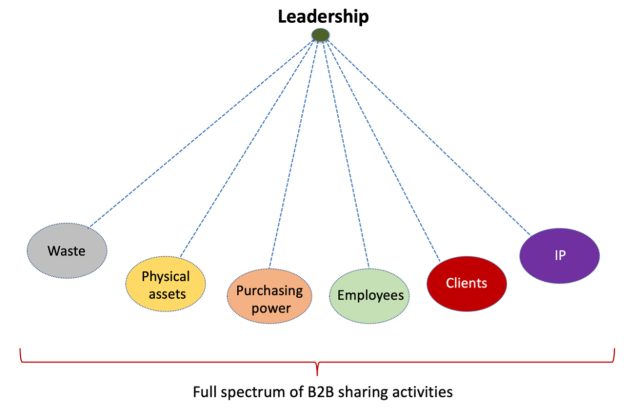

Navi Radjou then highlights the many potential benefits of this B2B sharing economy for social inclusion, the environment and health, especially if we know how to evolve from “smart sharing” to “wise sharing”. But to reap the benefits of this new dynamic without delay, it will not be enough to encourage companies to do it all by themselves: we must push public authorities to accelerate the movement. To this end, 10 innovative proposals are addressed to governments.

Introduction

The Great Recession of the late 2000s gave birth to the sharing economy, enabling individuals to use digital platforms like Uber, Airbnb, and BlaBlaCar to share their unused or underused cars and homes with others, thus generating additional income while maximizing the value of their assets.

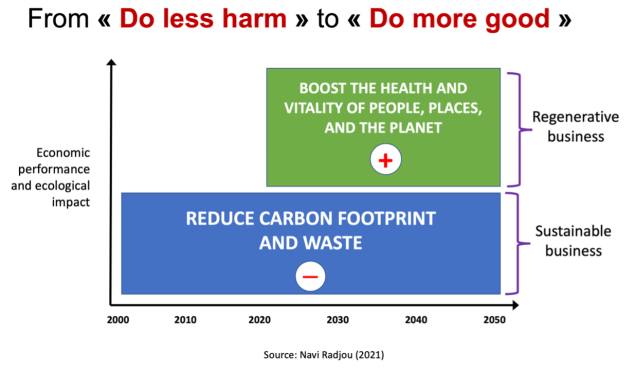

This peer-to-peer (P2P) or consumer-to-consumer (C2C) sharing economy took off so quickly that, in 2015, the audit and consulting firm PwC estimated that 18% of US adults had already partaken in the sharing economy as a consumer, and 7% had participated as a provider. PwC projected this C2C sharing economy to grow from US$ 15 billion in 2013 to a whopping US$ 335 billion by 2025.

In 2022, as the world emerges from COVID-19 and a global recession, what if businesses start sharing their physical and intangible resources with each other? Such a business-to-business (B2B) sharing economy, potentially worth trillions of dollars, is already emerging, fueled by greater environmental and social awareness and new technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT)[1].

Let me introduce you to some of the pioneers building this B2B sharing economy around the world:

Flowspace, FLEXE, and SpaceFill are cloud-based, on-demand warehousing networks that link up businesses seeking warehouse space with firms with underused storage space, enabling large companies as well as e-commerce startups to cost-effectively scale their distribution network and bring their products faster to customers.

Xometry, Fictiv, KREATIZE, and Hubs are on-demand manufacturing marketplaces that connect thousands of highly specialized machine shops with global businesses, thus empowering the small industrial firms to keep their factories fully utilized, especially during a downturn.

People + Work Connect and Hydres are two AI-powered employer-to-employer platforms that help people who are either laid off or want to expand their professional horizons with new experiences, quickly find work in another company.

Breather, LiquidSpace, and Ubiq enable companies to monetize their excess office space by renting it to other businesses on a short-term or a long-term basis.

Floow2 and Cohealo have built digital platforms that enable hospitals to share their medical equipment and services, thus maximizing their asset use and boosting patient care quality.

Les Deux Rives is a business district in central Paris where 30 co-located public and private sector organizations share office space, equipment, and services, and recycle/upcycle waste as a synergistic ecosystem.

Thestorefront.com, Appear Here, and WeArePopUp aim to become the Airbnb of retail by giving brands access to short term retail space—ideal for pop-up stores—at thousands of locations worldwide.

Yet2 and NineSigma help Fortune 500 firms, small and midsize enterprises and government R&D labs maximize the financial value of their intellectual property (IP) assets by licensing them to innovation-seeking organizations.

Convoy, Everoad, TruggHub, and Trella are the Uber for trucking: their AI-based freight networks automatically connect shippers with carriers to move millions of truckloads effectively, helping shippers reduce freight cost and enabling truck drivers to earn more.

As these examples show, by sharing their physical and intangible resources with each other companies can do better with less, that is increase their revenue and agility while drastically reduce their operating costs and waste.

The multiple business benefits of B2B sharing

By sharing resources, businesses can:

Avoid big capital investments. Rather than waste their precious capital to build new factories and warehouses, manufacturers can rapidly and cost-effectively expand their supply chain capabilities by leveraging on-demand industrial marketplaces like Xometry, Fictiv, and Hubs and flexible storage networks like SpaceFill and FLEXE.

Reduce operating costs. By pooling their buying power and signing collective long-term contracts with shared suppliers, firms can curb their operating expenses while stabilizing the supply of critical materials. For instance, Civica Rx is a nonprofit group in the US that aggregates 1,400 hospitals’ demand to reduce cost of generic drugs for all its members and their patients. Likewise, rather than sign a long-term costly commercial lease, companies can rent additional office space on demand from workplace sharing platforms like LiquidSpace and Ubiq.

Generate new revenue streams. 30% of all warehouse space in the US—and 50% in Asia—is unused at any time. In the 10 most populous US cities, the occupancy rate in office buildings is just 33%. 30% of trucks on European roads run empty. The owners of these underused facilities and vehicles can make money by renting them to other companies desperately seeking additional storage, workspace, or shipping capacity.

Maximize the value of intangible assets. In today’s knowledge economy, businesses can extract greater value from their intangible assets like intellectual property (patents, copyrights, and knowhow) by sharing them with others. Each year, US firms lose US$ 1 trillion in IP value as they lack a sound commercial strategy to monetize their inventions. IP-rich firms can leverage brokering services like yet2.com and NineSigma to generate profit from their unused intellectual assets like patents by sharing them with innovation-hungry businesses.

Boost agility and resilience. During COVID-19, as customer demand nosedived, small manufacturers were stuck with idle factory capacity. On-demand industrial marketplaces like Xometry and Laserhub make these small firms resilient by linking them up rapidly with new clients, so they keep their machine shops and employees fully utilized. Likewise, rather than be burdened with excess workforce during a downturn, companies can gain in agility by sharing temporarily their underused workers with other firms in search of talent.

Innovate faster, better, cheaper. 95% of new consumer products fail at launch as they don’t meet actual customer needs, leaving brands with costly unsold stock. Instead of guessing consumer preferences and mass-producing the wrong products faster, brands could use platforms such as Thestorefront and Appear Here to set up pop-up stores in multiple strategic locations to test a wide variety of new product concepts with customers. Brands can then selectively scale up the production of only those concepts that customers really like.

Satisfy customers seeking end-to-end solutions. Instead of point solutions, customers are seeking end-to-end tailored solutions from multiple brands that extensively address their broader needs. For instance, there is a growing need for point-to-point mobility solutions that seamlessly integrate carsharing, train and bus rides, and rental biking. By sharing and integrating data on their assets and customers with each other, companies from different sectors can synergistically deliver a seamless experience to their shared clients.

Given all these benefits, it’s not surprising that, according to a business.com survey, nearly 70% of companies today engage in the B2B sharing economy in one form or another at least once a month, with 26% using these services daily[2].

Given the very large volume of transactions it enables, B2B sharing could possibly unleash trillions of dollars in economic value, dwarfing the C2C sharing economy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: B2B sharing could dwarf the C2C sharing economy in volume and value

The social and ecological impact of B2B sharing

Beyond the purely economic gains for companies, B2B sharing can also have a major positive social impact, for several reasons.

First, B2B sharing networks and platforms catalyze the creation of new jobs, especially for marginalized groups, and help preserve local jobs in the states and territories. For example, Boomera, Bilum, and Rimagined are social businesses that collect used products and waste materials from other companies and “upcycle” them into beautiful new products. These firms employ disabled and underprivileged people in their value chain, hence regenerating local communities. Similarly, employee sharing and collaborative recruitment platforms like Mobiliwork and People + Work Connect avoid laying off underutilized workers and keep them fully employed by integrating them into other companies in the same region. In doing so, they also preserve valuable skills and know-how locally, hence avoiding a “brain drain”.

Second, B2B sharing enables artisans, small farmers, and small and medium enterprises (SMEs)—the most valuable and the most vulnerable segments of our economy—to increase their resilience, agility, and performance by gaining access to assets and skills from other companies at lower cost. For example, in India, the EM3 Agri Services online platform operates as an “Uber for small farmers”; it provides them access to tractors and other farm equipment as well as on-demand consulting services on a flexible pay-per-use basis. This frugal and flexible service enables India’s financially strapped farmers to produce better—and earn more—using fewer resources. Similarly, SMEs in underdeveloped regions can adapt to new digital realities and accelerate their green transition by hiring experts in technology and sustainability on a “shared time” basis from talent-sharing networks like Vénétis.

Third, B2B sharing can improve the well-being of all citizens. Take the example of digital platforms like Floow2 and Cohealo, which allow hospitals to share their medical equipment and services. Thanks to these platforms, anxious patients can get quality care faster by going directly to a hospital with the right equipment and readily available staff to treat them without delay. Similarly, with the majority of senior citizens wishing to remain at home as long as possible, companies and local authorities can share their expertise and pool their resources through multi-sector initiatives like InHome (see page 20) to co-create innovative solutions to improve the quality of life of seniors at home.

B2B sharing will also have a considerable positive impact on the environment. By merely getting all its companies to share their waste—through a process known as the Circular Economy[3]—each country can reduce its carbon emissions by 39%[4]. If companies go one step further and start sharing physical assets—inventory, spaces, vehicles, equipment—the environmental benefits could be significant.

Take the case of transportation, the second largest contributor of greenhouse gases in the world after energy and electricity production. Road freight transportation, which carries 95% of the products we consume every day, accounts for 6% of the European Union’s total CO2 emissions. In the US, heavy-duty trucks account for 20% of transportation-sector emissions. However, 35% of trucks circulating in the US and 30% of trucks on European roads today drive empty.

These “empty kilometers” (or “empty miles”) represent tens of millions of tons of CO2 every year. Digital freight networks such as Convoy, Everoad, TruggHub, and Trella seek to make trucking more efficient and sustainable by connecting companies that want to ship goods directly with carriers (mostly small businesses), without going through intermediaries. By 100% automating freight procurement, these AI-powered digital platforms optimize truck fill rates by grouping several shipments into a single task for a driver, thus massively reducing emissions related to empty miles. For instance, Convoy estimates its Automated Reloads program could help reduce empty-mile emissions by 45% in the US.

According to a study conducted in 8 European countries by BlaBlaCar, Europe’s leading consumer-to-consumer carpooling platform, its ride-sharing service saved more than 1.6 million tons of CO2 per year in 2019 alone—the equivalent of the emissions generated by transportation in Paris in one year—while transporting twice as many passengers.

Similarly, by adopting B2B carpooling and ridesharing services offered by players such as Klaxit, SPLT, BlaBlaCar Daily, OpenFleet, Sixt, Share Now, and Zipcar, businesses can significantly reduce the size of their vehicle fleet, offer flexible and affordable mobility solutions to their employees, and massively reduce their carbon footprint.

Here are three major B2B sharing initiatives launched in 2020, against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, that demonstrate powerfully the positive social impact that B2B sharing can achieve on a large scale in a region or an entire country:

China: In January 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed China, hundreds of hotels, cinemas, and restaurants shut down and thousands of their employees were either put on furlough or laid off. Meanwhile, Hema, a digitally savvy supermarket chain founded by Chinese billionaire Jack Ma’s Alibaba group, was facing a labor shortage as it struggled to keep up with a surge in online orders for groceries delivery. To solve its labor crunch, Hema entered into an employee-sharing agreement with caterers, hotels, cinemas, and restaurants to hire their idle workers on a short-term basis to prepare and deliver groceries. By late April 2020, 2,700 workers from 40 other companies were employed at Hema under the job-sharing plan. Inspired by Hema, other online retailers and supermarket chains in China like Ele, Carrefour, Wal-Mart, Meituan, JD’s 7Fresh also borrowed employees from restaurants and other businesses[5].

USA: On April 1, 2020, Ohio State Governor Mike DeWine announced the launch of the Ohio Manufacturing Alliance to Fight COVID-19 (OMAFC) to respond to the major shortage of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) like face shields, isolation gowns, and masks in the state. The OMAFC was co-led by The Ohio Manufacturers’ Association (OMA), the Ohio Manufacturing Extension Partnership (and its partner organization MAGNET), the Ohio Hospital Association, and JobsOhio[6].

The OMAFC acted as a large-scale B2B sharing platform by pooling demand data from hospitals and nursing homes from across Ohio to determine their specific PPE requirements and aggregating supply-side insights from 2,000 regional manufacturers to identify their existing capabilities and resources. MAGNET shared its engineering expertise with manufacturers to help retool their existing factories and repurpose their current products and materials to make PPE (for instance, ROE Dental Laboratory in Cleveland adapted its 3D printing facility to produce one million testing swabs and another group of manufacturers repurposed the plastics used in garbage bags to produce disposable gowns). JobsOhio offered regional support and financial assistance to scale up production and speed up delivery of PPE and other critical items to healthcare and frontline workers.

By rapidly connecting healthcare providers with thousands of regional manufacturers and widely sharing information, materials, and engineering expertise, the OMAFC enabled Ohio to fight COVID-19 with speed and efficacy by producing PPE at a cost-competitive price in the state without depending on other countries. For example, in mid-August 2020, the OMAFC announced it had successfully collaborated with Buckeye Mask and Stitches USA, two Ohio-based manufacturers, to repurpose their existing facilities and supply chains so they can co-effectively mass-produce 100,000 high-quality cotton face masks a day.

France: Situated in Southern France, Occitanie is the country’s second largest region. In November 2020, the France Industrie Occitanie collective, in collaboration with the regional administration, the DIRECCTE, and 10 industry trade federations in Occitanie launched Passerelles Industries. This scheme allows industrial companies in difficulty to temporarily lend their employees to other companies that are recruiting, thus preserving jobs and valuable expertise in the region. The labor-sharing program is available to 10,000 companies and 220,000 employees in the industrial sector in Occitanie. Passerelles Industries, which currently has 120 participating companies, has helped maintain many jobs and retain critical skills in the region.

B2B sharing offers very compelling economic, social, and ecological benefits. To fully reap these benefits, however, businesses in capitalistic societies must unlearn their old habits of hoarding resources and competing brutally with each other and learn to cooperate and share resources.

This radical change in attitude—and especially in mindset—will not happen overnight. Companies therefore need a strategic roadmap to gradually transform their culture and to integrate their organization ever more deeply into the fledgling B2B sharing economy.

Crawl and walk before you run in the B2B sharing economy

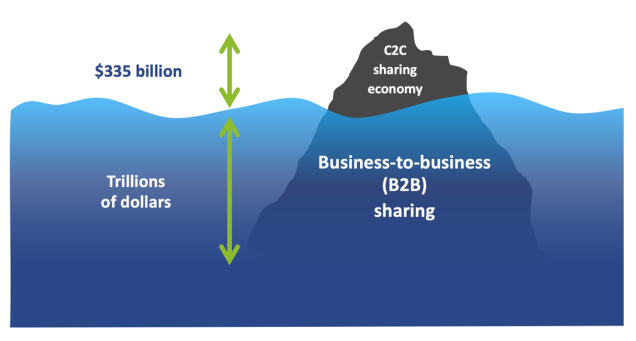

I propose a holistic framework (see Figure 2) that can serve both as a taxonomy to classify the various activities that take place in the B2B sharing economy as well as a “maturity model” to help businesses identify what strategies and capabilities they need to develop next to connect more deeply into the B2B sharing economy and achieve greater benefits.

As companies progress through each level, they will gain more self-confidence and learn to trust their peers in the B2B sharing economy. This, in turn, will encourage them to take more risk and share resources of even greater value and establish deeper strategic partnerships.

Figure 2: The B2B sharing taxonomy-cum-maturity model

Here is how businesses can learn to crawl and walk before they run in the B2B sharing world:

- Level 1: Sharing waste

A low-risk way for companies to get started with B2B sharing is by sharing waste, in a way that one company’s waste streams become the raw materials for another firm. In Denmark’s Kalundborg Eco-Industrial Park, for example, several co-located companies exchange material waste, energy and water as an integrated close-loop ecosystem. This process is known as industrial symbiosis. To date, the Kalundborg ecosystem has helped reduce annual CO2 emissions by 240,000 tons and water use by 3 million cubic meters.

Inspired by Kalundborg’s success, in 2003, the UK government launched the National Industrial Symbiosis Programme (NISP) to capture industrial opportunities from sharing energy, water, and waste materials. Working synergistically, the 15,000 corporate members of NISP collectively reduced carbon emissions by 42 million tons and redirected 48 million tons of waste from landfills for reuse, shrinking costs and creating over than £3 billion in revenue. The NISP found that each ton of CO2 saved costs members only around U$ 1, which is far less expensive than, say, carbon trading, with its high transaction cost.

In 2017, the European Union launched SCALER, an ambitious project to encourage 30 European regions to introduce industrial symbiosis practices in 500 manufacturing sites. The European market for industrial symbiosis is estimated to be worth more than €73 billion per year.

Companies can also use the principles of the circular economy to recycle or upcycle waste materials into new value-added products. For instance, Tarkett, a global leader in flooring solutions, recycles not only its own carpets but also those of other manufacturers, and uses the recycled materials to make new branded carpet tiles. And Bilum, a socially responsible French company founded by Hélène de La Moureyre, recovers used materials (Heineken cartons, Club Med boat sails, gendarmerie jackets, Air France life jackets) and “upcycles” them into beautiful, more valuable products such as bags, accessories, or furniture.

Level 2: Sharing physical assets

Businesses with unused or underexploited physical assets—such as inventory, spaces, buildings, equipment, vehicles—can share them with other firms seeking extra space, supplies, or operational resources. This way, companies can keep their physical assets fully utilized and generate additional income.

Europe will need 11.6 million square meters of additional storage space by the end of 2022. The French startup SpaceFill has developed an on-demand platform that allows owners of underutilized warehouses to generate new revenue by quickly renting them out to large corporations or e-commerce startups in dire need of storage space. Likewise, Headspace enables companies that own beautiful spaces to rent them to other businesses seeking inspiring venues to host their meetings and conferences.

Manufacturers with idle factories can offer their unused production capacity to other firms by using platforms like Xometry, KREATIVE, Fictiv, and Hubs. Digital freight networks like Convoy and Everoad help fleet operators keep their trucks fully utilized and earn more income by seamlessly combining loads from multiple shippers. The Cohealo platform enables US hospitals to share medical equipment with each other, thus reducing capital expenses, increasing availability, and improving patient care[7]. Construction companies in Belgium use Floow2 to share their unused construction materials and machines with their peers.

70% of French citizens go to work by car and spend an average of 6,049 euros per year to maintain their car. 70% of these home-to-work trips are made alone. Private cars contribute to almost 16% of greenhouse gas emissions in France. Public transportation is not practical for all workers, as 40% of French people live in an area poorly served by buses and trains. Inspired by the great success of BlaBlaCar, which facilitates carpooling between individuals, the startups Klaxit and Karos have built carpooling networks dedicated to companies, offering their employees a sustainable, comfortable, user-friendly, and frugal mobility solution. Klaxit and Karos alone facilitate more than 3 million home-to-work carpools per day. Karos estimates that, thanks to its carpooling services, its business users save an average of 2 full tanks of gas per month and 26 minutes per trip.

Some businesses may be wary of sharing their physical assets in a marketplace that enable anonymous many-to-many relationships. These firms can get their feet wet in the B2B sharing economy by establishing a strategic partnership with just one trusted company and share their assets exclusively with that firm first before engaging with other partners.

For instance, Ericsson teamed up with Philips to combine city street lighting with mobile-phone infrastructure. Integrating cell-phone antennae into energy-efficient LED streetlights installed across a city helps carriers increase their network coverage in that city. Similarly, rival chocolate makers Hershey and Ferrero made a deal to share warehousing and transport assets and systems across North America, thus curbing the number of distribution trips and reducing CO2 emissions.

Large enterprises, like industrial conglomerates, can also jumpstart their B2B sharing journey by first sharing physical assets among internal units and trusted partners within their own ecosystem. For instance, since 2018, the energy giant Engie has piloted BeeWe, a collaborative economy platform that enables supply chain professionals among various Engie entities to pool and share industrial spare parts with each other. This cuts the need to produce costly new industrial parts and boosts the speed and agility of maintenance services. BeeWe already offers 180,000 items worth 100 million euros in total and is used by 4,200 employees globally across the Engie group.

At level 1 and level 2, B2B sharing operates mainly as a transactional marketplace, connecting many cost-conscious “buyers” with multiple “providers” who want to monetize their underused physical assets and material resources on a short-term, tactical basis.

It should be noted here that « bartering » (or “barter”) is also part of this logic of transactional exchanges at levels 1 and 2. Bartering is the exchange of goods or services between companies without the use of cash. Bartering is a common business practice in Anglo-Saxon countries, Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, Greece and developing countries. Now, companies in countries like France and Canada have also embraced bartering. In France, there are two well-established platforms—KORP and BarterLink—that facilitate inter-company bartering based on a virtual currency. In Canada, the BarterPay community boasts 4,155 businesses that have conducted 630 million transactions, saving Can$ 212 million in cash. Bartering is legally, accountably, and fiscally authorized in many countries, including the US, France, Australia, and Canada.

From level 3 on, however, companies transcend the purely commercial logic and short-term financial interest. They move beyond tactical transactional exchanges of tangible goods and services that take place in an anonymous “marketplace”. Instead, firms begin to establish strategic partnerships with a select group of deeply trusted peers, forming strategic B2B sharing communities. Members of these close-knit communities pool and share highly valuable and intangible resources to co-create long-term economic value and positive social and ecological impact at a large scale[8].

Level 3: Sharing purchasing power

Pooling buying power isn’t new. For instance, government agencies as well as retailers form “purchasing cooperatives” that aggregate demand to get lower prices from select suppliers. But enlightened organizations can pool buying power to not only reduce the costs of procurement but also to increase their agility and resilience. In doing so, they can ensure the steady supply of critical goods that suffer from high price volatility and risk being disrupted by cataclysmic events like COVID-19 and climate change. In addition, these firms can boost their innovation capacity and contribute to the common good.

Consider the healthcare sector. U.S. hospitals are experiencing chronic drug shortages. 121 life-saving drugs are currently out of stock and 70% of hospital pharmacists face more than 50 shortages per year. These shortages are typically caused by product recalls, unexpected supply chain disruptions such as COVID-19 (80% of active pharmaceutical components in U.S. drugs are sourced from China and India), or a big spike in demand during flu season or epidemics. In 2019 alone, U.S. hospitals had to invest 8.6 million in additional work hours, at a cost of US$ 360 million, to deal with drug shortages.

In addition to shortages, hospitals in the U.S. also face drastic drug price increases. In the first half of 2019 alone, the average price of more than 3,400 drugs rose by 10.5 percent, or five times the rate of inflation. Hospital must also contend with wild price swings—when a generic drug company breaks the price of a drug to wipe out its competitors, then drastically hikes the price, leaving hospitals and patients at its mercy.

Fed up with drug shortages and price gouging dictated by the pharmaceutical industry, more than 50 health systems representing more than 1,400 hospitals and 30 percent of hospital beds in the U.S. have joined forces to form Civica Rx, a nonprofit organization that ensures a steady supply of quality drugs at a lower price for all its members. Civica Rx has pooled the buying power of its more than 50 members to negotiate a long-term agreement with generic drug manufacturers such as Xellia, Exela Pharma Sciences and Hikma to produce over 50 essential generic drugs at a fair and stable price and to supply them without interruption for several years.

All of these drugs are being produced in the U.S., reducing dependence on global supply chains exposed to disruptions caused by pandemics like COVID-19, natural disasters related to climate change, or geopolitical tensions with China. Civica Rx is also a boon for insurers, as it could save payers potentially US$ 1 billion a year in drug costs. To date, 23 million patients across the U.S. have been treated with Civica Rx medications.

Dan Liljenquist, member of Civica Rx’s board of directors, explained to me that by pooling the purchasing power of 1,400 hospitals, Civica Rx wants to serve a noble purpose: to make drugs affordable and accessible to all Americans, which Liljenquist considers as their birthright. Civica Rx therefore embodies wise sharing, a model of enlightened B2B sharing in the service of the common good (we will expound this notion of wise sharing in the last section of this report).

My research shows that B2B sharing has grown considerably in countries all over the world during to the public health and economic crisis of 2020–21. Yet, the majority of companies currently practice B2B sharing at levels 1, 2, and 3. We can refer to these three levels collectively as “basic B2B sharing”. I strongly believe, however, that all nations can achieve significant economic, societal, and ecological gains by encouraging their businesses to progress to levels 4, 5, and 6 of B2B sharing, what I call “advanced B2B sharing”.

Level 4: Sharing employees

Companies can also share their human resources with one another, enabling them to gain access to a broader and more diverse pool of talent, skills, and expertise.

The 2015 Eurofound report identifies two kinds of employee sharing[9] :

Strategic employee sharing: a group of businesses form a network that recruits one or more workers on a full-time basis and sends them on individual job assignments to the member firms.

For instance, Vénétis is an association of 360 small French businesses that hires experts — in fields as diverse as industrial quality control and web marketing — as full-time employees and shares them on a project basis among its member firms, thus replacing precarious part-time jobs with safe, “shared-time” jobs.

Ad hoc (tactical) employee sharing: a business that is unable to offer work for its employees temporarily “loans” them to another company, with full consent of the workers. This temporary mobility of workers is a win-win-win model. By loaning out underemployed employees, the lending company can maintain their employability, preserve valuable skills, and reduce personnel costs. The “host” business wins by gaining access to motivated and directly operational staff at lower cost. The employee is also a winner because he (she) maintains her employment contract with his employer and 100% of his remuneration while diversifying and enriching her professional career in new work environments.

In France, digital platforms like Mobiliwork, laponi, and Pilgreem facilitate ad hoc (temporary) employee sharing among companies with the same or across different sectors. In the UK, the New Anglia Advanced Manufacturing and Engineering group (NAAME) and the Cambridge Norwich Tech Corridor launched the Talent Sharing Platform (TSP) in early 2021. TSP enables engineering and manufacturing businesses within the East Anglia region to share their technical staff temporarily or “to co-employ niche expertise that may not be required on a permanent basis by an individual company.” TSP was set up to help businesses in East Anglia mitigate the negative impact of both COVID-19 and Brexit.

The twin health and economic crises in 2020 validated the value and merit of the talent sharing model on a grand scale and accelerated its wider adoption among businesses. For example, in April 2020, when COVID-19 was in full swing in the US, Accenture, Lincoln Financial Group, ServiceNow, and Verizon jointly launched People + Work Connect, an artificial intelligence (AI)-based employer-to-employer platform that helps people laid off at one company quickly find employment at another organization, breaking the long and traumatic cycle of unemployment for these workers.

Platforms like People + Work Connect and Hydres could also support the rise of the “boomerang” employee, i.e., an employee who works 3 to 5 years in a company and leaves it to come back, enriched with new skills and already familiar with the company’s culture. This is a win-win model for both the employee and the employer[10]. In the US, 94% of senior executives are willing to rehire a former employee and 52% of workers won’t mind rejoining a former employer. In France, 22% of companies re-hired former employees during 2020.

Companies that feel too nervous to share their employees with other businesses can first experiment it safely within their own organization. The global consultancy Deloitte, with nearly 335,000 employees in over 150 countries, did just that. Deloitte teamed up with Freelancer.com, the world’s largest freelancing and crowdsourcing marketplace, to set up MyGigs, an internal talent-sharing platform for its global employees.

MyGigs automatically matches employees with relevant skills with specific work projects. When managers need urgently a special skill for a project, they post their requirements on MyGigs and interested employees can bid to work on that project. MyGigs boosts employee motivation and engagement for two reasons. First, it enables multi-talented employees to apply their various skills in several projects across different practice areas—so a risk management specialist in the insurance practice can lend her deep operations research skills to optimize a supply chain project in the automotive practice. Second, MyGigs gives global exposure to Deloitte employees, so a London-based consultant can work on projects led by teams in Bangalore or Shanghai.

Over 20,000 Deloitte consultants are already using MyGigs. Deloitte plans to get 20% of its global workforce to use this service. Once Deloitte has tested and validated talent sharing internally, it intends to extend it externally, by connecting MyGigs to Freelancer’s 56 million-strong global virtual workforce.

The various employee-sharing mechanisms described above could deliver “flexicurity”—a synergistic balance of flexibility and security that will be highly valued by both employers and workers in the 21st century[11].

Level 5: Sharing clients

Competitively minded businesses have traditionally sought new ways to lock customers into their brands by building vertical ecosystems. But building a brand-specific ecosystem has become meaningless and even counterproductive today, as digitally empowered Millennials and Generation Z customers can create their own personalized products without depending on established brands.

Given this new trend, visionary brands are forming horizontal ecosystems that integrate their capabilities and assets with those of other brands—including their rivals—to offer their “shared clients” end-to-end solutions and highly personalized experiences.

For instance, Orange, Kingfisher, Carrefour, Legrand, La Poste, SEB and Pernod Ricard—seven leading companies from seven diverse industries—set up InHome, a cross-industry innovation incubator run by InProcess, an innovation consultancy. Through InProcess’ ethnographic studies, InHome member firms first gain deeper insights into the future needs and values of typical families who will be living in tomorrow’s homes. They then consider effective ways to integrate their respective offerings and core competences to synergistically serve their common customer of their future.

By participating in multi-sector innovation projects like InHome focused on the shared customers of tomorrow, explains Christophe Rebours, founder and CEO of InProcess, businesses competing directly in a capitalist market can unlearn their « competitive instincts » and cultivate the spirit of cooperation. “Companies are able to take off their ‘industry blinkers’ and see things from the point of view of their shared client; it is no longer increasing their own piece of the pie that motivates them but increasing the size of the whole pie for the benefit of all, ” elaborates Rebours.

In coming years, McKinsey & Company predicts the rapid erosion of traditional industry boundaries and the rise of cross-sectoral digital ecosystems that deliver fully integrated, end-to-end customer experience. By 2025, the revenues flowing through these cross-industry ecosystems could exceed US$ 60 trillion—or 30% of the combined revenue of global businesses[12]. Unless bricks-and-mortar companies in established industries learn to join forces and co-develop cross-sectoral digital solutions for their shared clients, they will miss out on this US$ 60 trillion market opportunity, for the benefit of digital giants like GAFA.

Level 6: Sharing intellectual property (IP)

Patents, ideas, best practices, and domain knowledge are the crown jewels of an organization. As a result, a company may be reluctant to share its intellectual property (IP) with other companies. However, it may make sense to do so for two reasons.

First, companies can monetize their unused or underutilized intellectual assets by sharing them. In the US, intangible assets account for 90% of the market value of the S&P 500 (the 500 US firms with the largest market capitalization). Each year, the U.S. generates more than US$ 6 trillion in intellectual property (IP)—patents, copyrights, and know-how. Yet, US$ 1 trillion of it is wasted annually as U.S. businesses lack a clear plan to obtain maximum value from their IP, such as new technology inventions. Likewise, according to the European Commission’s PatVal-EU study, 36% of European patents have not been commercially exploited. Companies can better leverage these under-utilized patents, and generate new revenues, by exchanging them on IP sharing platforms such as yet2.com and NineSigma with other innovation-seeking firms.

Second, progressive companies driven by a higher purpose can achieve “moral leadership” in their industry by sharing their IP with other organizations—including rival firms—to increase the collective social and ecological impact of their industry.

For example, R&D teams at consumer goods giant Unilever and apparel maker Levi Strauss had invented proprietary technologies to make their products more sustainable. Unilever’s “compressed deodorants” use 25% less aluminum and half the amount of propellant, reducing the carbon footprint of each aerosol by 25%. Levi Strauss has developed 21 techniques to reduce water consumption by up to 96% in garment finishing. After deploying these green technologies successfully in their own supply chains first, these two firms have ‘open-sourced’ their inventions with the aim of raising the environmental performance of their entire industry.

Likewise, in 2019, the food giant Danone made its collection of 1,800 yogurt strains—including 193 lactic and bifidobacteria ferment strains—freely available to researchers around the world. In doing so, Danone wants to promote “open science” and help the world achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) faster, especially those related to ending hunger and improving nutrition and health.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, enlightened healthcare providers have shared their IP with other companies to co-innovate life-saving solutions. For instance, in March 2020, the medical device firm Ventec Life Systems shared the technology of its multifunction critical care ventilators with US carmaker GM. Both firms worked closely to rapidly scale up production of this life-saving device in a repurposed GM-factory in Indiana. Similarly, the industrial giant Siemens teamed up with Medtronic, a world leader in medical technology, to co-develop a “digital twin” of a ventilator and made it available as open source on the Internet so that anyone in the world could use it to make their own ventilators to help local COVID-19 patients.

As businesses share first their waste and physical assets, then their financial and human resources, and finally their clients and intellectual property with others, they will gradually build up their self-confidence and train their “trust muscle” as they learn to crawl, walk, and finally run in the B2B sharing world. B2B sharing could be the lynchpin of “stakeholder capitalism” and help us build inclusive, resilient, and regenerative societies in the post-COVID-19 era[13].

Mastery of all B2B sharing activities will maximize their value

At this juncture, it’s critical to clarify two key elements about the taxonomy-cum-maturity model of B2B sharing depicted in Figure 2 and expounded in the section above:

1) Although this framework has 6 distinct levels, it does not imply a hierarchy. Sharing intellectual property (IP) isn’t “better” or “superior” in any way than sharing waste. Likewise, the fact that a company shares its IP—the top rung in the maturity ladder—doesn’t mean it mastered the art of B2B sharing. The masters of B2B sharing are not the firms that can leap to—and remain at—the top of the pyramid depicted in Figure 2. Rather, the winning companies that will lead their industries are those that have mastered—and keep practicing in a dynamic and synergistic manner—the full spectrum of B2B sharing activities.

2) The various resources classified in Figure 2 are categorized by the level of general risk they carry if they were to be shared with other firms, rather than their intrinsic economic value. As such, sharing a low-risk resource like waste could also be highly valuable, that is financially very lucrative, if a company performs it strategically. Take the Tata Group, a global conglomerate with over US$ 100 billion in revenue headquartered in India that is comprised of 30 companies including Tata Steel and Tata Motors, which owns Jaguar Land Rover (JLR).

Tata Group companies are masters at turning waste into gold. Tata Steel, for instance, generated over US$ 35 million in 2018 alone by selling the 1.8 million tons of slag generated annually in its steel factory in India to other companies who use it as a raw material to build roads and produce cement and bricks. Likewise, as part of its journey to zero emissions, JLR has launched Reality, a bold enterprise-wide initiative to recover aluminum from used consumer products like drinks cans and aerosols as well as end-of-life vehicles and upcycle it to manufacture new vehicles, including an all-electric car.

Considering these two clarifications, the Figure 3 below shows what industry leadership in the 21st century entails: winning firms will be those that can deftly navigate through and master the full spectrum of B2B sharing activities. In doing so, leading firms will be able to unleash and capture the full value of B2B sharing.

How nations can unlock the full potential of B2B sharing

The World Bank has warned that the COVID-19 pandemic could spell a “lost decade” in economic growth. Rather than rebuild the dysfunctional capitalist economic system, which has caused severe inequalities and environmental destruction, nations could wisely use the next decade to construct a virtuous frugal economy that is socially inclusive and regenerates people, places, and the planet[14]. B2B sharing would be a key pillar of this frugal economy. However, to unlock B2B sharing’s full potential and maximize its economic, social, and ecological impact, nations would need two critical elements: a noble purpose and proactive government support.

A noble purpose will broaden B2B sharing’s impact

So far in this report we addressed the “what” and “how” of B2B sharing, that is the different mechanisms through which businesses can share their various types of resources. But companies must also address the vital “why” question, that is “why does our company want to engage in B2B sharing?”. In other words, companies need to get their motivation right and make sense of—and give meaning to—their commitment to this path.

If, to the “why?” question, most companies answer, “we want to save money or make more money”, we will see the rise of what I call “smart B2B sharing” whose narrow purpose is to solely make the current capitalistic economic system, with all its deleterious dysfunctions, even more efficient. But if most businesses answer “we want to make a positive social and ecological impact” then they can enable “wise B2B sharing” whose noble purpose is to radically reinvent entire industries and accelerate the transition to a benign frugal economy in the post-COVID-19 world (See Figure 4 below.)

Here are a few noble objectives that can motivate businesses to practice B2B sharing wisely and positively impact people, communities, and the planet.

Reinventing healthcare. B2B sharing can deliver a big shot in the arm for the financially stretched healthcare systems worldwide reeling under spikes of COVID-19 cases and struggling to deliver better care to more patients at lower cost. This is especially the case in the US, where skyrocketing healthcare spending will account for nearly 20% of GDP in 2026, which is unsustainable, even as more Americans get sicker.

By leveraging platforms like Floow2 and Cohealo to share medical equipment and services and pooling purchasing power through initiatives like Civica Rx, hospitals and clinics can effectively transition to Value-Based Health Care (VBHC), which is “an integrated care strategy focused on the value delivered to the patient.[15]” In the VBHC model, currently being implemented in the U.S. and Switzerland, multiple providers combine their resources and capabilities to optimize the care pathways and health outcomes for their shared patients. With pricing based on the quality, not the quantity, of care provided to the patient, VBHC aims to improve care delivery while reducing healthcare costs.

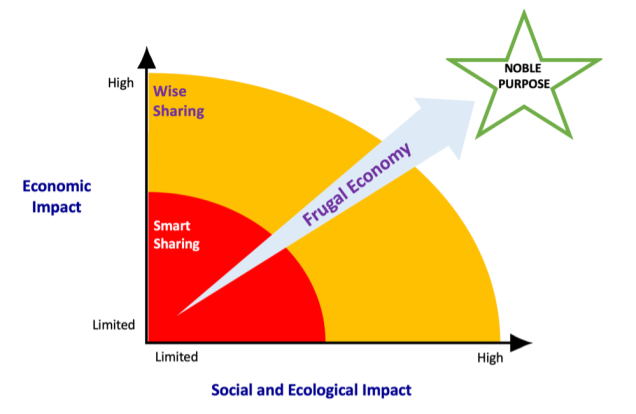

Going well beyond sustainability and regenerate entire sectors and regions. In recent years, many major companies—from Apple and Google to Tata Group and Siemens to Procter & Gamble and HSBC—have committed to becoming “carbon neutral” by 2030, 2040, or even 2050 (note that, as of now, only 32% of Fortune 500 have committed to climate targets and only half of those are aiming for zero emissions). The European Union aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) and to become carbon neutral by 2050. Upon taking office, U.S. President Joe Biden announced that the U.S. will reduce its emissions by 50–52% by 2030, compared to 1995, and become “net zero” (carbon neutral) by 2050.

In November 2021, at the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow, many political leaders made new engagements to drastically reduce their countries’ emissions—like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi who committed his country to becoming carbon neutral in…2070. The media lauded these “bold” engagements. But Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environment Program (UNEP), noted with sarcasm: “When you look at these new (COP 26) pledges, frankly, it’s the elephant giving birth to a mouse. We are not doing enough[16]”

Andersen is right. Given the climate emergency, companies need to boldly go far beyond the bland concept of “sustainability”. Recycling waste and reducing their carbon footprint isn’t enough. Firms need to quickly adopt the principles of regeneration, a set of science-based practices that aim to reverse global warming by, for example, sequestering carbon in products and processes. While a sustainable company is just focused reducing its carbon footprint and waste (negative impact), a regenerative business is consciously aiming to expand its positive social-ecological footprint—that is, “do more good”—by boosting the health and vitality of people, places (communities) and the planet (see Figure 5).

In doing so, regenerative businesses can achieve far greater financial performance and social and environmental impact than their peers who simply focus on sustainability[17]. A ReGenFriends study shows that 80% of consumers prefer “regenerative” companies to “sustainable” firms (they find the term “sustainable” too passive). Nevertheless, consumers express frustration with companies that lack regenerative expertise.

I can personally attest to the serious lack of awareness of, let alone expertise in, regeneration in many large companies. In 2019, I spoke at two conferences attended by R&D and supply chain leaders from three hundred Fortune 500 companies (the 500 largest revenue companies in the U.S.). When I asked them, “How many of you have heard of the concept of regeneration?” only 5% raised their hands! If I had asked them how many of them are actively implementing the principles of regeneration in their firms, probably only 1% would have raised their hands!

The good news is that pioneering companies like Danone, Eileen Fisher, General Mills, Interface, Marks & Spencer, Microsoft, Natura, Patagonia, and Unilever have already begun the regenerative revolution in America, Europe, South America, and around the world. These vanguard firms are seeking not to limit but to reverse global warming by investing, among other things, in innovative solutions to capture carbon.

For example, Interface, the world’s largest manufacturer of modular carpet, is reinventing its entire value chain and products to be regenerative. It is building a “Factory as a Forest” that not only has a zero-carbon footprint, but also produces free “ecosystem services” such as water storage, clean energy, clean air, and nutrient recycling that benefit local communities. With its Climate Take Back initiative, Interface is going beyond carbon neutrality and plans to sell only “carbon negative” products, which it has already begun marketing since late 2020.

The bad news is that these forward-thinking companies, for the most part, are adopting regeneration principles with a capitalist logic to generate more profit and to achieve “competitive differentiation”, that is to set their products and brands apart from those of their rivals in the competitive marketplace. As a senior manager of an industrial company acknowledges: “(By adopting regeneration), we will generate more revenue. We will steal market share from our competitors. We will also steal their customers and employees because we sell green(er) products that have purpose while our rivals only sell conventional products.”

Companies are often criticized for “green-washing” and “purpose-washing”. It is true that many companies “talk” about sustainability and “purpose” but do little to act on it. Yet, as the above quote indicates, a greater danger to our planet is “green-hoarding” and “purpose-hoarding”. In other words, a handful of visionary companies are actually “doing” something to reverse climate change, but are jealously guarding their innovations (technologies, best practices) in regeneration and are reluctant to share their intellectual property with other companies, especially their competitors.

These pioneering firms that are truly and boldly acting for the climate must not do so selfishly, i.e., with the sole aim of boosting solely their own company performance and gaining a competitive advantage over their competitors. Instead, they must widen their perspective and pursue a noble objective: “We will decarbonize our entire industry and regenerate the entire planet.” These companies must emulate Levi Strauss and Unilever, who generously share their green technologies with their rivals, with the firm belief that “a rising tide lifts all boats”.

As the head of sustainability at one enlightened industrial company told me, “We have developed disruptive technologies to make carbon-negative products from biomaterials. We want to share these technologies with our competitors because our goal is to contribute to the decarbonization of the entire built environment, which accounts for 40% of annual global emissions. In addition, the adoption of our technologies by our rivals will create increased demand for regenerative products, which will ultimately benefit the entire industry. Everyone wins.”

Audacious companies can go further and embrace B2B sharing, especially at levels 4, 5, and 6, to achieve an even higher goal: regenerating entire cities or territories. This is the case of the Italian company Illy, renowned for its coffee. Already fully committed to regenerative agriculture, Illy has joined forces with other Italian businesses and institutional players in the Parma region, as well as NGOs, think tanks, and foundations to form Regeneration 20|30. This initiative, under the patronage of the European Commission and led by the Regenerative Society Foundation, aims to create a regenerative economy in Parma and other regions that would maximize the well-being of all citizens while respecting planetary limits.

Achieving SDGs faster, better, cheaper. The United Nations has defined 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), all of which aim to co-construct inclusive, healthy, and regenerative communities around the world by 2030. If implemented, the SDGs could generate US$ 12 trillion in economic value per year and create up to 380 million jobs by 2030 worldwide. Yet to realize this potential, annual investments of US$ 5–7 trillion will be required to implement the SDGs globally. Unfortunately, developing countries face a US$ 2.5 trillion funding gap. Moreover, with rising inequality and climate change, the struggling world cannot afford to wait until 2030 to achieve the SDGs.

Wise B2B sharing practices can help achieve SDGs faster, better, and cheaper. For instance, in Africa, Coca-Cola shares its supply chain expertise and assets with nonprofit organizations that, for instance, piggyback on Coca-Cola’s cold-chain to deliver life-saving medicine like vaccines safely and promptly to remote villages. And by sharing their intellectual property with others—as Danone is doing—food companies can eliminate hunger globally and ensure that 8 billion people worldwide have access to safe and nutritious food.

Proactive government support can turbocharge B2B sharing

Governments can play a vital role in fostering B2B sharing. A decade ago, governments worldwide were caught by surprise by the explosive growth of the consumer-to-consumer (C2C) sharing economy, fueled by digital platforms like Airbnb and Uber. But this time around they can anticipate—and shape—the dynamics of the B2B sharing market. Policy makers at the national, regional, and local levels need to proactively identify the regulatory needs associated with B2B sharing and instead of curtailing its growth they can wisely leverage it to unlock huge economic, social, and ecological benefits for their cities, regions, and countries.

To catalyze B2B sharing in their countries, governments need to institute a comprehensive new regulatory framework and offer generous tax incentives that stimulate the sharing of physical and intangible assets among companies. This would include the deregulation or rewriting of rules covering critical areas such as legal liability, taxation, IP protection and workers’ rights.

Here are 10 concrete measures governments can take to boost B2B sharing in their countries:

- Officially recognize B2B sharing as one of the fundamental pillars of the national post-COVID-19 economic recovery plan—like the German Recovery and Resilience Plan (DARP) and France 2030—making it possible to accelerate the economic, ecological, industrial, societal, and social transformations of the country by 2030. B2B sharing, practiced at a large scale across a nation, could generate hundreds of thousands of new jobs, revitalize entire sectors, make territories resilient and thriving, and help achieve carbon neutrality not in 2040 or 2050, but even earlier.

The European Commission must encourage its member countries to sustain the B2B sharing practices that emerged during the COVID-19 crisis and scale them up in the post-pandemic era. The European Union (EU) was created in 1951 on the very basis of B2B sharing—by pooling the production of coal and steel across six West European countries. Coal and steel powered EU’s industrial growth during the 19th and 20th centuries. As we progress into the 21st century, it’s time for the EU to harness information and communication technologies (ICT) to power its services-led economic transformation. Digital B2B sharing platforms could help EU countries better integrate their economies that are increasingly “dematerialized” and boost their individual and collective performance.

During the Great Recession, the U.S. initiated the C2C sharing economy, which today is dominated by Silicon Valley giants such as Uber and Airbnb, which practice smart sharing aimed solely at economic efficiency. In the post-COVID-19 era, Europe could catalyze wise sharing, supporting a decentralized B2B sharing economy that would facilitate social inclusion and accelerate the ecological transition in all regions of Europe. To do so, the European Commission must incorporate B2B sharing as a key element in the European Green Deal action plan.

- Relax existing labor laws to enable employee-sharing among companies. Some countries did just that during COVID-19, but on a temporary basis. For instance, on June 17, 2020, the French government passed a law, known as “Emergency Law 2”, to facilitate le prêt de main-d’oeuvre (labor lending) between companies. In mid-December 2020, France extended this derogation to existing labor laws until June 30, 2021. The May 31, 2021, French law on the “management of the end of the health crisis” extended this arrangement until September 30, 2021. By making this derogation permanent—or by enacting new laws that induce “flexicurity” in the labor market—countries could stimulate employee sharing between companies and accelerate inclusive economic growth. Employee sharing will also help alleviate the severe labor shortage now experienced by many countries around the world as they strive to reboot their economies after COVID-19.

- Educate and inspire business and political leaders at the national, regional, and local levels on the economic, social, and ecological gains of B2B sharing by establishing a dedicated website which would document inspiring case studies and identify proven best practices in terms of B2B sharing from across the state or nation. For instance, the European Commission could set up B2Bsharing.eu to showcase inter-company sharing of resources in various EU member countries. Likewise, the state government of California, home to Uber and Airbnb, can launch B2Bsharing.ca.gov to inspire regional companies to share their assets and capabilities and encourage Silicon Valley players to build safe digital platforms to enable B2B sharing.

Visionary governments could judiciously integrate employee-sharing as a key mechanism of their “career transition” support programs—like “Collective Transitions” (Transco) in France—which enable employers to anticipate economic and technology changes, identify jobs at risk, and proactively support the retraining and reskilling of their employees.

- Ask the central banks and tax authorities to officially recognize—and monitor—the transactions taking place on B2B sharing platforms and networks. This is already the case for bartering exchanges. For instance, the US and Canadian governments both recognize bartering—the direct exchange of goods and services between companies without using money—as a legal form of commerce. Their tax authorities recognize bartering exchanges such as IMS and BarterPay as “third-party record keepers”, like banks and brokerages, and ask them to report all barter transactions among its clients. The same regulatory and fiscal framework needs to be extended to on-demand digital marketplaces that enable B2B sharing.

On 3 July 2020, the OECD released its Model Rules for reporting of data by platform operators with respect to sellers in the sharing and gig economy. The Model Rules require “operators of digital platforms to collect information on the income earned by those offering accommodation, transport and personal services through platforms and to report the information to tax authorities”[18]. On 22 June 2021, the OECD amended these rules by adding an international exchange framework and extending the rules’ scope to the sale of goods and transportation rental services.

Similarly, the European Union (EU) member countries have adopted rules revising the Directive on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation, thus extending the EU tax transparency rules reporting by digital platforms on their sellers (DAC7). This Directive will go into effect from 1 January 2023.

The OECD’s Model Rules and the EU’s DAC7 presently cover only transactions in consumer-to-consumer (C2C) sharing economy. The OECD and the EU need to proactively extend the scope of these rules and directive to B2B sharing activities as well.

- Encourage the state and local economic development agencies, cooperative banks, and credit unions to invest in existing B2B sharing ecosystems at the state (regional) and city levels to accelerate their growth. During COVID-19, businesses in many regions and cities worldwide launched ad-hoc B2B sharing marketplaces and networks, which can be formalized and scaled up with financial support of state and local governments and community-focused banks. Specifically, government bodies like the Small Business Administration (SBA) in the US and India’s MSME can set up B2B sharing platforms and networks for the benefit of small and medium enterprises, which form the backbone of our economies.

- Push the national agencies like the US Patent and Trademark Office and the UK’s Intellectual Property Office, which today help companies protect their original ideas and inventions with patents, to also educate and encourage businesses to maximize the value of their intellectual property (IP) by sharing it with other companies. These agencies must understand that IP stands not only for “intellectual property” but also for “intellectual partnering” in our interconnected global digital economy.

- Lead by example to inspire businesses to practice wise B2B sharing to positively impact society and the planet. For instance, governments can show companies how to wisely pool their purchasing power to do better with less, that is to achieve economic gains through the volume effect but also to improve the social impact and environmental performance of companies. The State can set an example by supporting grouped purchases in the public sector that have virtuous effects at the societal and ecological levels.

For instance, in France, the national association of local authorities (AdCF) and the French union of purchasing groups (UGAP) jointly published a groundbreaking legal note in October 2019. This note explains how the mutualization of public procurement can accelerate the circular economy and the ecological transition in the territories. But governments worldwide can go one step further. They can raise the bar by publishing a new guide in 2022 that would explain how cities and regions can use mutualized public sourcing as a strategic lever to go beyond mere “sustainable development” and support a regenerative local economy (this is already the case in Occitanie, a region in Southern France, which has an ambition to become Europe’s first Positive Energy Region by 2050).

- Ask the Competition Authority to promote innovation by opposing the lobbying efforts of trade unions and professional bodies in the country that would seek to block the rise of B2B sharing practices in certain sectors. For instance, in September 2021, the Autorité de la concurrence, France’s national competition regulator, sanctioned several large road freight transport players for organizing a boycott against Fretlink, Everoad, Chronotruck and Shippeo. These four startups aim, with their digital B2B sharing platforms, to optimize freight transport and massively reduce their ecological impact. It’s worth noting that the French regulators, in explaining their ruling in favor of these B2B sharing startups, cited both the increased economic and environmental benefits that these digital platforms could potentially bring to their clients.

- Use B2B sharing as a “carrot” to incent businesses to share data. Data is the new oil. Data is becoming vital to the growth of our economy and the well-being of our society[19]. Sadly, businesses have not unlocked the full value of data. The main reason is data silos. Each company and each industry hoards jealously its operational and customer data safely behind firewalls. We have “islands of data” across our economy, but they are not interconnected due to safety concerns. An Everis study funded by the European Commission shows that only 39% of European businesses share data with other firms. The main reasons others don’t are privacy concerns (49%) and fear of misappropriation by others (33%)[20].

- And yet, OECD studies shows that data access and sharing can boost the value of data for holders, generate 10 to 20 times more value for data users, and create 20 to 50 times more value for the whole economy. The OECD estimates that the sharing of private-sector data can unlock social and economic gains worth between 1% and 2.5% of GDP[21].

The European Union is working on two regulatory measures—the Data Governance Act and the Data Act—to encourage businesses to share data safely and seamlessly and unlock the full socio-economic value of B2B data sharing. Likewise, the UK’s National Data Strategy aims at “building a world-leading data economy while ensuring public trust in data use.” Both the EU and the UK are also massively investing in technology-based solutions like “data spaces” and “data safe havens” to boost data safety and facilitate data sharing.

All these government measures, however, are missing the point: they put “the policy and technology cart before the motivation horse[22].” Indeed, the Everis/European Commission study cited above reveals that the two greatest motivations for companies to share data are “the possibility to develop new business models and/or new products and services” and “the possibility to establish partnerships with other companies interested in my data”. As such, governments must share the findings of this report with businesses to show them how they can collectively unlock trillions of dollars in economic value and achieve massive social impact by pooling and sharing their physical and financial resources, employees, clients, and IP. This will incent businesses to rapidly commit to—and adopt—the new policies and technology solutions that governments are developing to boost B2B data sharing.

- Position B2B sharing as a key pillar of a new paradigm for foreign policy and international cooperation. This is especially the case for Western countries. For a long time, it was believed that the rich countries in the Global North innovated and the poor nations in the Global South imitated and copied. The era of “North-South technology transfer” is over. Today, it is the South that innovates faster, better and at lower cost, and it’s the turn of the North to learn from the South. Across Africa, India, and South America, thousands of entrepreneurs and companies are practicing frugal innovation: they are using B2B sharing ingeniously to co-create inclusive and sustainable solutions with limited resources[23].

For example, competing telecom operators have long shared cell towers in Africa and India, accelerating the adoption of mobile finance, distance learning, and mobile health in those regions. And farmers in India, Africa and South America are using digital knowledge platforms like Digital Green and WeFarm to share agricultural best practices and innovations directly with each other.

Given this new global reality, the international development agencies in the West—like USAID, Agence Française de Développement (France), Department for International Development (UK), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (Germany), must reinvent themselves as “co-development” agencies. They should actively engage innovators in the West and in emerging countries to co-develop B2B sharing platforms that would benefit all nations[24]. Western nations would then truly embody the new paradigm of “North-South co-creation” advocated by Jean-Yves Le Drian, the French Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs, who said: “It is no longer a question of doing things for the countries of the South, but with them (…), because the challenges we face are common challenges.[25]”

The countries whose governments proactively implement all these measures well will shape and lead the global B2B sharing market, potentially worth trillions of dollars, by creating demand for it and by reinforcing the supply-side capabilities.

***

Just as the financial crisis of 2008 spawned the US$ 335 billion-worth consumer-to-consumer (C2C) sharing economy, the COVID-19 pandemic has already catalyzed the rise of a multi-trillion-dollar B2B sharing economy, poised for exponential growth in coming years.

By wisely sharing their tangible resources and intangible assets with each other, purpose-driven businesses can make immense gains in efficiency and agility, innovate faster and better, and positively contribute to communities and the planet. The B2B sharing revolution promises to not only upend industries and reinvent our economies but also help us build inclusive and regenerative societies in the post-COVID-19 word.

[1] In an article published in Fast Company on April 14, 2021, the author describes the emergence of this B2B sharing economy and its key business benefits and identifies the key players who are building it: https://www.fastcompany.com/90624859/the-sharing-economys-next-target-business-to-business

[2] The State of the B2B Sharing Economy, Business.com: https://www.business.com/articles/b2b-sharing-economy/

[3] In today’s linear economy, we continuously extract natural resources and transform them into new products which, after their initial use, end up as waste in landfills. In contrast, a circular economy aims to reuse products and recycle waste again and again in a closed-loop system, hence reducing the need for more resources.

[4] Source: https://www.circularity-gap.world/2021

[5] Two seminal academic papers by Hui-Wen Chuah et al. and Chen, Z. explore the business dynamics and the societal impact of the emerging B2B sharing economy in China and examine its public policy implications: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921344921005012#! https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.714704/full

[6] To learn more on the Ohio Manufacturing Alliance to Fight COVID-19 (OMAFC) visit https://repurposingproject.com

[7] The Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KP-SC) health system uses the Cohealo platform to share over 100 types of medical equipment used by 10 service lines in 27 facilities throughout KP-SC. Dr. Ronald Loo, who initiated this sharing program, estimates that KP-SC saved the purchase price of a lithotripsy machine in just 1 year by sharing it with other facilities. Source: OR Manager, June 2020.

[8] It’s important to differentiate “B2B sharing”, which is a broader concept, from “B2B sharing economy”, which is a specific application domain of inter-company collaboration. When companies share resources within a formal economic structure like an exchange or a (digital) marketplace—transacting as anonymous “buyers” and “sellers” motivated mainly to optimize their individual financial interests—they participate in a B2B sharing economy. But companies can also share resources within a preestablished, small, trusted community with a primary goal of co-creating value for all members and achieving positive social and ecological impact. This report, as conveyed in its title, examines the dynamics of B2B sharing in general as well as the B2B sharing economy specifically. The purpose of this report is to help companies share their resources effectively to co-create not only “shared value” but also “shared values” in our societies.

[9] “Employee sharing”—where an employee of one company is shared (temporarily) with another company—should not be confused with “work sharing”—where two people are employed on a part-time or reduced-time basis to fulfill a job usually performed by one person working full-time.

[10] A longitudinal study of 2,053 boomerangs (workers returning to their original employer) over an eight-year period in a large health care organization shows that after being (re)hired into the organization, boomerangs tend to outperform new hires. Source: “In with the Old? Examining When Boomerang Employees Outperform New Hires”, Academy of Management Journal (2020).

[11] “Flexicurity” is a proactive labor market policy that delivers employers the flexibility to thrive in rapidly changing economy while safeguarding the welfare of employees. Flexicurity was first implemented successfully in Denmark. Its success inspired the European Commission to integrate flexicurity into its employment strategies. Flexicurity is a key component of the French labor reforms enacted by President Emmanuel Macron in 2017. Prof Ton Wilthagen at Tilburg University has researched and published widely on flexicurity as a sustainable labor policy and a source of social cohesion: https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/persons/ton-wilthagen

[12] “Competing in a world of sectors without borders”, McKinsey & Company (2017).

[13] Unlike shareholder capitalism that focuses narrowly on short-term profit optimization for shareholders, stakeholder capitalism is a virtuous economic model in which businesses seek long-term value creation by considering the needs of all their stakeholders, thus benefiting society at large: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/01/klaus-schwab-on-what-is-stakeholder-capitalism-history-relevance/

[14] The frugal economy operates under the general principle of “doing better with less”. It consists in better meeting the socio-economic needs of all citizens by using the least amount of resources necessary. Source: Radjou, N., “The Rising Frugal Economy”, MIT Sloan Management Review, August 6, 2020.

[15] The concept of Value Based Healthcare (VBHC), introduced in 1966 by Avedis Donabedian, a physician and professor at the University of Michigan, was later expounded by Michael Porter, a professor of management at Harvard Business School, in a book co-authored in 2006 with Elizabeth O. Teisberg, Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-based Competition on Results.

[16] “Despite COP26 pledges, world still on track for dire warming”, The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2021/11/09/cop26-un-emissions-gap/

[17] Radjou, N. “Beyond Sustainability: The Regenerative Business”, Forbes, October 24, 2020.

[18] Source: https://www.oecd.org/ctp/exchange-of-tax-information/model-rules-for-reporting-by-platform-operators-with-respect-to-sellers-in-the-sharing-and-gig-economy.htm

[19] The Value of Data – Policy Implications – Main Report (2020), Bennett Institute for Public Policy, University of Cambridge: https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/publications/value-data-policy-implications/

[20] Study on data sharing between companies in Europe: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/8b8776ff-4834–11e8-be1d-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[21] Economic and social benefits of data access and data sharing, OECD: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/90ebc73d-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/90ebc73d-en

[22] “Policymakers want businesses to share more data. How might it work?”, Tech Monitor: https://techmonitor.ai/policy/digital-economy/policymakers-want-businesses-to-share-more-data-how-might-it-work

[23] Radjou, N., “Frugal innovation : a pioneering strategy from the South”, A Planet for Life (2014), published by IDDRI : http://regardssurlaterre.com/en/frugal-innovation-pioneering-strategy-south

[24] We are entering the Age of Convergence in which there are no longer « problems of the North » on one side and « problems of the South » on the other. Humanity as a whole is grappling with what I call « problems without borders »—epidemics, social inequalities, global warming, the scarcity of natural resources (agricultural land, water)— that now affect everyone on the planet. It is time for Western nations to transcend the artificial « North-South » divide and assume global leadership by co-creating with developing countries « solutions without borders » to address the socio-economic and ecological challenges that will seriously affect all humans in the coming decades.

[25] Statement made by Jean-Yves Le Drian, French Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs Europe, at the International Cooperation Meetings, a virtual event organized by Expertise France on February 9, 2021: https://www.euractiv.com/section/development-policy/news/france-announces-development-aid-boost/

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5