For the freedom to have control of one’s body – Promoting and ensuring access to women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights in sub-Saharan Africa

Twenty-six years after the World Conference on Women’s Rights in Beijing, the Generation Equality Forum marks a crucial new stage in governments’ commitment to gender equality. The fight for gender equality remains an open issue at the international level. In a quarter of a century, there have been no new international texts to back up the previous commitments. Worse, the defence of women’s rights is hampered in many international forums by motley coalitions of governments that deny, for various reasons, the discrimination suffered by women. In cultural, social and religious contexts, women are denied control over their own bodies.

At the same time, the understanding of the mechanisms of discrimination against women has increased. The freedom to have control of one’s own body is often narrowly understood as the choice to procreate. But it is really about a wider set of rights, that are independent of each other, without which there is no autonomous choice or real equality: access to education and information, access to health care systems, access to contraceptive methods, access to legal and safe abortion, protection against sexual violence, such as rape, female genital mutilation, of child marriage, forced marriage, etc.

These rights form a continuum now referred to as Sexual and Reproductive and Health Rights (SRHR). The promotion of these rights, which faces many obstacles in the multilateral international framework, is the subject of particular mobilization by a broad coalition of governments, of which France is a member. In Paris, France, which is co-chairing the Generation Equality Forum with Mexico, will be particularly involved in the coalition on « Bodily Autonomy and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights ». This commitment, consistent with the affirmation of feminist diplomacy over the past several years, has raised substantial expectations on the part of many civil society organizations and partner countries involved in gender equality. To be fully mobilizing, this French commitment must be translated into a specific financial effort within the framework of official development assistance. Budgetary choices, from this point of view, have fallen short of the message’s objectives.

A strengthening of the French commitment is all the more necessary as the health and security contexts are deteriorating in the regions where it counts. Women’s and girls’ rights are particularly vulnerable to the security, political, economic and cultural vagaries of societies experienced in sub-Saharan African countries on a daily basis. We have observed that, as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, advances in sexual and reproductive health and rights are difficult to achieve and their decline is particularly severe when access to the school system is made impossible, when the health care system is disorganized, when local associations no longer have the resources to carry out their actions, or when such rights are even directly hindered by certain social forces or by political or religious leaders. The resulting gender inequalities perpetuate and reinforce violence against women and girls.

However, if women and adolescent girls are denied the right to take control of their bodies, the repercussions are not limited to the loss of bodily autonomy. It is their entire emancipation journey that is at stake, with multiple impacts that concern their entire lives. These barriers threaten their future and the possibility of aspiring to a full education and economic independence, and deprive them of rights as basic as the right to health and security. In short, they deprive them of a fundamental universal right, their freedom and their right to choose.

It is therefore essential that societies and policy makers are made aware of the importance of promoting access to SRHR for women and girls and that funding in this area continues and is increased. This is why France’s official development assistance for SRHR in sub-Saharan Africa is essential to bring about tangible and continuous change on the ground with a view to guaranteeing these rights.

This report gives a voice to actors in the field who are developing concrete programmes to promote SRHR in five sub-Saharan African countries (Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Democratic Republic of Congo, Senegal). Thanks to numerous interviews with political and institutional leaders, representatives of local NGOs based in the five countries studied and French feminist associations, the work group identified several levers for action that still need to be developed to enable women to assert their rights.

The report makes six recommendations to the French government regarding funding for sexual and reproductive health and rights in sub-Saharan Africa:

1. Increase French funding for SRHR

2. Cover the full range of SRHR issues to meet needs on the ground: a priority for respecting women’s and girls’ fundamental rights

3. Simplify the process of identifying and accounting for funding for SRHR

4. Favour the funding of projects with a long timeframe

5. Adapt funding eligibility procedures for local and feminist NGOs

6. Invest in the potential of youth.

For the freedom to have control of one’s bodyPromoting and ensuring accessto women’s sexual and reproductive healthand rights in sub-Saharan Africa

This report written by Deborah Rouach was produced by a working group consisting of Amandine Clavaud , Juliette Clavière and Alexandre Minet for the Jean-Jaurès Foundation , and Suzanne Gorge and Marc-Olivier Padis for Terra Nova .

Executive summary

LIST OF ACRONYMS

AFD : French Development Agency

AU : African Union

CNJFL : Nigerian Cell of Young Female Leaders

CSE : Comprehensive sexuality education

CSO : Civil society organisation

DAC : Development Assistance Committee

DRC : Democratic Republic of Congo

FFM : French Muskoka Fund

FGM : Female genital mutilation

FP : Family planning

GBV : Gender-based violence

GEF : Generation Equality Forum

GNI : Gross National Income

HDI : Human Development Index

HIV : Human immunodeficiency virus

NGO : Non-governmental organisation

ODA : Official development assistance

OECD : Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

RMNCH : Reproductive, maternal, new-born and child health

RMNCAH : Reproductive, maternal, new-born, child and adolescent health

SDG : Sustainable development goal

SRH : Sexual and reproductive health

SRHR : Sexual and reproductive health and rights

STI : Sexually transmitted infection

UN : United Nations

UNFPA : United Nations Population Fund

FOREWORD

2021 represents a pivotal year for the defence of women’s and girls’ rights, especially the right to have control over their bodies. Indeed, while the coronavirus crisis has exacerbated the fragility of health services around the world, attacks on the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) [1] of women and girls are increasing and threatening to undermine and violate these fundamental rights in many parts of the world.

The holding of the Generation Equality Forum (GEF) in Mexico City in March 2021 and in Paris in June 2021 puts the defence of gender equality at the heart of the international political agenda and is therefore a major event. Although it does not aim to adopt a normative text, the Generation Equality Forum provides a framework for discussion for governments, civil society, the private sector and all individuals and organizations involved in the defence of women’s rights. It also provides the framework for concrete commitments by the participants, including the French government, which has taken a « champion » position within the coalition on the subject of SRHR.

To get around the blockages of multilateral negotiations, the Generation Equality Forum proposes an alternative method through « action coalitions » which bring together on an equal footing a multitude of private and public actors from all over the world whose representations and political actions converge. The issue of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) will be specifically addressed in one of these action coalitions, a significant stance given that since the 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing, “no international conference or discussion on this [topic] has been deemed possible by governments and civil society, for fear of a negative effect on these rights” [2] . Indeed, in the absence of a political perspective and international consensus on SRHR, addressing this issue within the framework of the Generation Equality Forum can reinforce initiatives involving a wide range of actors.

The format of the Generation Equality Forum marks a number of departures from traditional international diplomacy. This is not a multi-stakeholder framework that is binding on all stakeholders, but a voluntary participation that allows for collaboration between partners. In this way, it promotes innovation, concrete steps and financial commitments to achieve this and ensure a wider outreach beyond governmental bodies. France, given its historic role as an advocate for women’s right to have control over their own bodies and as a donor of official development assistance to Africa, should be encouraged to make concrete, sustainable commitments to sexual and reproductive health and rights at the Generation Equality Forum.

Introduction

On 8 March 2021, on the occasion of International Women’s Rights Day, Phumzile-Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women declared: "While progress has been made over the past twenty-five years, no country has achieved gender equality” [3] . Moreover, according to initial assessments of the current health crisis, the latter is resulting in a significant decline in SRHR: “47 million women could lose access to contraception, resulting in 7 million unwanted pregnancies [4] ”.

Yet gender equality and women’s sexual and reproductive health (SRH) are recognized as fundamental rights by international bodies. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 1979, the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action in 1995, a world conference on women’s rights, whose twenty-sixth anniversary the Generation Equality Forum (GEF) will celebrate, and the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) formulated as part of the 2030 Agenda, are founding texts in this field. However, the subject of SRHR is a source of much tension both within governments and at the international level. In multilateral bodies, some governments are challenging the recognition of these rights and the implementation of programmes to support them. Even within civil society, religious representatives defend representations of the family and the procreative role of women that go against freedom of choice. This is why there is a power struggle between governments and within intergovernmental organizations over the protection rights of women’s right to bodily autonomy. In the absence of consensus, it is proving extremely difficult to obtain the adoption of binding commitments in favour of SRHR.

There are significant disparities in access to SRHR across the world. France is strongly committed to raising the profile of this issue at the international level and to promoting comprehensive, long-term progress in SRHR in developing countries where France is involved and where the needs are highest, notably in sub-Saharan Africa. The integration of the SRHR concept into the French government’s official language dates back to the 2010s. For a long time, development aid policies focused on protecting mother and child health, but the official discourse then shifted to a demographic dividend approach [5] for sub-Saharan Africa. This discourse, which often led to a demographic “risk” being highlighted, could be seen as a form of interference from another era by France’s partners. More recently, France has prioritized SRHR in the framework document L’Action extérieure de la France sur les enjeux de population, de droits sexuels et reproductifs 2016–2020 [6] , demonstrating a change in perspective, in line with recommendations from civil society organizations (CSOs). This new approach is part of the promotion of a feminist diplomacy upheld by France. As part of its co-chairing of the Generation Equality Forum with Mexico and its leadership of the “Bodily Autonomy and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights” coalition, concrete commitments are expected from France to initiate tangible changes in terms of gender equality and access to SRHR for the next five years.

This report therefore analyses the implications of this new diplomatic approach, in particular French financial commitment to SRHR in five sub-Saharan African countries: Mali, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Niger and the Democratic Republic of Congo [7] . In these countries, the rights of girls and women to bodily autonomy are fragile, threatened and even violated. These are inalienable rights of women that are essential for their empowerment. SRHR are a crucial element in achieving gender equality and ensuring an equitable future for a population as a whole. In an often-dramatic context for girls and women in this region, this report reiterates the need to actively promote and defend free access to SRHR and comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) for women and the general population. We also study the multiple economic, cultural, religious, security and health crisis-related obstacles against which a broad mobilization of governments and civil societies is, more than ever, necessary. Finally, we give actors mobilized in the field an opportunity to express themselves, who emphasize the importance of the approach in terms of access to rights to support aspirations and change in these countries. The report concludes with six recommendations to the French government regarding its official development assistance for SRHR in sub-Saharan Africa.

1. ADDRESSING SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS PRIORITIES IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA [8]

A. DEFINITION OF SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS

First of all, it should be noted that the very notion of SRHR represents progress in that it considers these rights as a whole, taking a holistic approach [9] . SRHR bring together a set of different but complementary concepts. It is the notion of linking a health approach with a freedom approach through access to a certain number of rights. SRHR therefore include sexual health, reproductive health, sexual rights, and reproductive rights. The issues to which these concepts refer are multiple and can be broken down as follows:

– family planning

– having control over one’s own body

– the right to choose whether or not to have sexual relations, when and whom to marry, whether or not to have a child, how many children to have and when to have them

– access to sexual and reproductive health care

– the right to safe and legal abortion

– respect for the integrity of the body, i.e. the fight against female genital mutilation and all other forms of gender-based sexual violence

– access to comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) and information on SRHR

– information about all SRHR issues

– the right to a safe sex life, i.e. combating sexually transmitted infections and diseases (STIs)

Source for table: Recommendations for the ICPD beyond 2014: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for All, High-level Task Force for the International Conference on Population

and Development (ICPD), High-Level Task Force for ICPD, 2013, p.4.

Because of the intertwining of these themes, the term « care continuum » is used. This expression makes it possible to promote an integrated, cross-cutting approach to SRHR perceived as a whole without hierarchy and without exclusion. This approach emphasises a continuum of care and of information provided about SRHR, starting in childhood, through the school system, and aimed at the whole population without discrimination on the basis of gender, age, religion or social class. It puts forward a conception of SRHR in which the well-being of women and girls is seen as a whole, that includes physical, mental, emotional and social well-being. The decompartmentalization of SRH care services is another feature of this approach and responds to the realities of bodily autonomy where needs cannot be segmented as they are so plural and often linked to each other.

As a result, commitment to SRHR does not translate into a single type of programme or support action, but rather a multiplicity of programmes addressing each aspect. SRHR therefore imply both a diversity of commitments and a coherence to be sought across all these programmes. Access to education and health systems is the basis of this approach, but it is implemented through projects of varying scales and sometimes very targeted, small-scale field actions that nevertheless have a decisive impact on the target populations.

B. PRESENTATION OF THE REGIONAL CONTEXT IN TERMS OF SRHR

Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the regions in the world where access to SRH services and women’s right to control their own bodies is most precarious. The patriarchal organization of societies shapes mentalities and participation in social life and the full exercise of rights are limited by multiple forms of gender inequality and discrimination against women and girls.

In addition, the region suffers from a severe lack of resources to meet a high demand. This reinforces the infringements on the integrity of these rights. These can take the form of child marriage or forced marriage for adult women, pregnancy in a minor and/or unwanted pregnancy, female genital mutilation (FGM), gender-based sexual violence (GBV), and also an insufficiency or absence of SRH care (prevention, information, the fight against STIs, comprehensive sexuality education, lack of care, follow-up and management during pregnancy, childbirth and the neonatal and postnatal period, etc.). These denials of rights for adolescent girls and women are barriers to their independence and affect their entire lives.

In Central and West Africa, populations are facing multiple crises. Among them, the security situation in some of the countries studied constitutes a considerable obstacle to compliance with SRHR. Women and girls in conflict zones are exposed to war-related violence and in particular to sexual violence (rape, genital mutilation, prostitution, etc.). Insecurity therefore has major repercussions on access to care and information on SRHR and consequently on respect for women’s bodily autonomy. Mali, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Niger and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), are all theatres, at different levels, of violence with terrible consequences for their populations. The resources devoted to stabilizing areas of conflict and fighting terrorism mean that basic public services, such as those relating to health, are lacking or non-existent and that people are deprived. SRH services are directly affected by insecurity and political instability, which hinder the establishment of effective, long-term health programmes. Moreover, regions that are difficult to access or dangerous are abandoned both by members of associations and NGOs worried about the attacks [11] that they could suffer because of their actions relating to SRHR, and by donors who fear a lack of transparency in the use of funding.

In West Africa, between 2007 and 2018, only 38% of adolescent girls and women aged 15 to 49 were able to make their own decisions about health, contraception and sex with their partners or spouses, three criteria which characterize bodily autonomy [12] . However, this figure drops drastically when looking at the countries in our study with 7% for Senegal and Niger, 8% for Mali and 20% for Burkina Faso [13] . The DRC is closer to the average for Central Africa (33%) with 31% of women and girls aged 15 to 49 declaring that they had bodily autonomy [14] . For the period 2015–2019, more than 6.5 million unwanted pregnancies were recorded in West Africa [15] . In addition, according to Guttmacher data [16] , between 2015 and 2019, 8 million abortions were performed in sub-Saharan Africa, three quarters of which were unsafe, possibly resulting in medical complications or even death. In Burkina Faso, 72% of abortions were performed by non-medical staff, as were 63% of abortions in Senegal.

The legislative framework for SRHR in West and Central Africa

The establishment of a legal framework would appear to be a prerequisite for ensuring an environment where women and girls’ rights are protected. Regional treaties have been adopted to ensure a favourable legal framework for the respect of SRHR in the region. For example, the Maputo Protocol signed in 2003 by the African Union (AU) to promote equal rights for girls and women recognizes abortion as a fundamental right in cases where the pregnancy is the result of rape, incest, endangers the woman’s mental and physical health or her life, and if the foetus has dangerous abnormalities.

In 2011, the Ouagadougou Partnership [17] was created between the nine French-speaking West African countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal and Togo, and donors, including the French Development Agency (AFD), to establish and strengthen family planning (FP). The aim is to enable wider use of contraception and to coordinate projects between countries and their funding partners. These treaties are especially important as they consolidate uniform legislation to protect the rights of women and girls across the region.

However, governments’ commitments under these regional treaties are not always transposed into national law. This is particularly the case for the DRC, which had signed the Maputo Protocol without publishing it in its Official Gazette , thereby impeding its application by the countries’ courts. It was not until 2018 that this transcription of the Maputo Protocol was adopted and that it took precedence over national law. However, it remains relatively unknown by the population. In Senegal, the protocol has been transposed into the country’s law, but local associations note that it is not respected [18] .

The legal framework is thus still far from homogeneous across the region, as illustrated by the case of abortion legislation (see box on following page). Even when the law allows abortion under certain conditions, its application continues to be a struggle and access to a medical center or competent personnel remains difficult. Access to contraception and the whole SRHR package also depend on the policy in each country.

Legal continuum | Southern Africa | Central Africa | East Africa | West Africa |

(N=5) | (N=9) | (N=18) | (N=16) | |

HIGHLY RESTRICTIVE LAWS | ||||

Category 1 | Angola | Mauritania | ||

Madagascar | Senegal | |||

None | Republic of Congo | |||

Sierra Leone | ||||

Malawi | Côte d’Ivoire ® | |||

Category 2 | Uganda | |||

Gambia (F) | ||||

To save a woman’s | Gabon (R, I, F)* | Somalia | ||

Mali (R, I) | ||||

life | South Sudan | |||

Nigeria | ||||

Tanzania | ||||

MODERATELY RESTRICTIVE LAWS | ||||

Category 3 | Burundi | Chad (R, I, F)* | ||

Comoros | ||||

To save a woman’s | Cameroon ® | Burkina Faso (R, I, F) | ||

Djibouti | ||||

life and preserve | Lesotho (R, I, F) | Equatorial Guinea +, ++ | Guinea (R, I, F)* | |

her health (without explicit mention | Ethiopia (R,I, F)** | |||

Central African Republic (R,I, F)* | Niger (F) | |||

of mental | Kenya | Togo (R, I, F) | ||

health) | ||||

Zimbabwe (R, I, F) | ||||

Category 4 | Eritrea (R, I)* | |||

To save a woman’s | Botswana (R, I, F) | DRC (R, I, F) | Mauritius (R, I, F) ++ | Ghana (R, I, F) |

life and preserve | Eswatini (R, I, F) | Mozambique (R, I, F)* | ||

her health (with explicit mention | Chad (R, I, F) | Liberia (R, I, F) | ||

Namibia (R, I, F) | Rwanda (R, I, F)* | |||

of mental | ||||

health) | Seychelles (R, I, F) | |||

BROADLY LIBERAL LAWS | ||||

Category 5 | ||||

To save a woman’s | ||||

life and preserve her | Zambia (F) | |||

(physical and/or | ||||

mental) health and for | ||||

socio-economic reasons | ||||

Category 6 | ||||

No restriction as to | Cape Verde § | |||

reason (with legal | South Africa § | Sao Tome and Principe § | ||

limits on gestational | Guinea-Bissau | |||

period and other | ||||

legal requirements) | ||||

Distribution of sub-Saharan African countries by sub-region and laws governing abortion

Most common additional reasons:

R = rape, I = incest; F = severe foetal impairment

Underage girls are eligible | + Marital consent required | ++ Parental consent/notification required | § Gestational limit of 12 weeks for abortions on request | ** No gestational limit specified for abortions on request.

NB: Many laws defining the legal basis for abortion are independent of a country’s categorization on the legal continuum. The most common are those that allow abortion in cases of rape, incest, or severe foetal impairment; these are listed here for the four categories for which these additional reasons logically apply. DRC = Democratic Republic of Congo. Sources: References 20–23.

Source: Akinrinola Bankole et al, From unsafe to safe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa: slow but steady progress, Guttmacher Institute, 2020

In Mali, for example, the law requires the signature of three doctors before an abortion can be performed, making access difficult, which is already restrictive within the legal timeframe, especially since doctors invoke the conscience clause. In Burkina Faso, it is necessary to wait for a court ruling that rape or incest has resulted in a pregnancy, with the result that the time period for a legal abortion cannot be respected [19] .

The heterogeneity of the legislative frameworks in the countries studied also works against women’s rights. This can be seen, for example, in the fight against gender-based violence. Mali is the only country in the region that does not prohibit gender-based violence, thereby allowing practices such as female genital mutilation to continue unimpeded. It suffices to take a woman from Senegal, Niger or Burkino Faso over the border to enable female genital mutilation take place. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) report, 86% of Malian women aged 15 to 19 were mutilated between 2004 and 2018. Forty-five per cent of women aged 15 to 49 have experienced physical and/or sexual violence, according to the National Institute of Statistics in Mali [20] .

Another challenge is access to information about the legislation, as populations have little information or knowledge about SRH laws and therefore their rights in this area. In Senegal, the law on reproductive health dates from 2005 and allows, women to decide freely and with discernment the number of their children and the spacing of their births. It also implies the right to have the necessary information, the right to better health for all and the right to the services provided for this purpose” [21] . However, local associations consider that it is not being implemented [22] . In Mali, there is a law on SRH adopted in 2002 guaranteeing access to family planning and prohibiting the refusal to prescribe or force the use of contraception on a person of any age. This law also remains little-known by the population [23] .

Moreover, where legislative frameworks exist in favour of SRHR in the countries studied, they are nevertheless hampered by the weight of traditions, which are sometimes reinforced by a regional security context that continues to deteriorate. Gender-based violence against women and girls can also take the form of forced marriages and underage marriages, which constitute a major obstacle to women’s empowerment. According to the UNFPA report, 39% of girls are married before they reach the age of majority in Central and West Africa [24] .

Source : Unicef, La situation des enfants dans le monde, 2016. Infographie : Le Figaro.

These practices particularly affect the most vulnerable, such as internally displaced persons and those living in conflict zones. Marriages of minors are most often carried out for economic reasons by families unable to provide for their children and lead to many early pregnancies and forced marriages. In 2020, 5.5 million people were internally displaced in the DRC, the largest number in the world [26] . These people living in camps constitute a segment of the population at risk due to the loss of their usual environment, the break in family and social ties linked to displacement and the increased weight of the community within the camp. This is why they are targeted and integrated into the actions by NGOs that implement awareness-raising sessions on SRH. Governments are also working with external partners to implement national plans to address the specific needs of these populations and develop integrated SRH services.

In Niger, the law allows girls to marry at the age of fifteen, compared to eighteen for boys, but they are often married at twelve [27] . The main explanation lies in the customs and honour dimension of marriage for families who want to avoid an out-of-wedlock pregnancy at all costs [28] . It should also be taken into account that having a large number of children in a household is perceived as being good for a family’s reputation. Moreover, in a context of great poverty, marriage is seen as a path to economic prosperity and improved social status within the community. Finally, despite progress in schooling, marriage still often appears to many families as the only possible choice for girls [29] .

The weight of customs and religion

There are many barriers to the development of SRHR in this region. Sometimes linked to political contingencies and the agendas of political leaders, they are also the consequence of a very strong prevalence of religious rules and a patriarchal vision of society.

Indeed, some governments and politicians have not made gender equality a priority in public policies, and in particular SRHR which touch on subjects that are still taboo in societies and which crystallize debates. When an area of SRHR is taken into account by the authorities, they prefer to use semantics that diminish the scope of the subject matter, for example, comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is referred to as “family life education” in Burkina Faso.

Governments or political figures who favour SRHR may be criticized or even threatened by segments of society and influential conservative groups such as some religious and community leaders. In Senegal, for example, religious lobbies are active in the government and block progressive discourse on legalizing abortion in cases of rape and incest and on sexual and reproductive health in general.

In Mali, where the population is 90% Muslim, several initiatives related to SRHR have been cancelled. An attempt to include SRH issues in school textbooks was denounced by some religious leaders to President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta; they argued that the “acceptance of differences” in the textbooks would encourage homosexuality [30] . The Malian government was obliged to abandon the project. In 2021, the draft law against gender-based violence proposed by Bintou Founé Samaké, the Minister for the Promotion of Women, Children and the Family, suffered the same fate.

According to the NGO, the Pananetugri Women’s Well-Being Initiative, in Burkina Faso, “in 2018 the Minister of Health, Nicolas Meda, raised the idea of granting the right to safe abortion with the President of the National Assembly. Once this was publicly reported in the press, there were strong reactions forcing the government to retract the suggestion". [31] Thus, in the face of traditions and pressure from a section of society and some religious leaders, attempts at legislation are thwarted and SRHR are passed over in silence. It is crucial to convince elected politicians that investing in health and SRHR is a right and a need, but above all a long-term investment that must be defended against prevailing traditions and customs. [32]

The influence of traditional and religious leaders and traditional rules on society can be seen in the daily lives of citizens, in the public space and in power relationships. In Burkina Faso, the chefferie (chieftainship) is omnipresent in the rural territories of the Centre and East, is no less absent from the major urban centres. However, their influence expresses less a replacement of the public authorities than a superposition of moral, sacred, and sometimes political authorities. For foreign and local NGOs, and for international representatives, any visit and/or implementation of projects must be preceded by a preliminary exchange with traditional and religious authorities, in order to introduce themselves and to foster acceptance and ownership of the project. This protocol ceremony is carried out in addition to the one that nevertheless retains primacy, with the local political authorities (governor, president of regional councils, mayor, etc.).

“Every time we go on a mission outside the capital of Burkina Faso, we first visit the administrative, political, traditional and religious authorities to present the reason for our presence and our mission. The religious authorities have a major influence on society” [33] . Moreover, “representatives of traditional and religious authorities are members of the Global Fund’s Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM) for grants to defeat HIV, TB and malaria, along with France and other partners” [34] .

Community and religious leaders, who are almost always men, have a significant influence on people’s personal lives and how everyday matters are conducted. Women and girls are therefore particularly vulnerable in geographical areas where religious and cultural values weigh heavily on people’s lives. Many religious and conservative communities define acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. They perpetuate unequal and discriminatory gender roles for women and girls who must be subservient to the head of the family and fulfil their function as wives and mothers 1 . Marrying and having children, in this case, is not a woman’s choice, but a duty. In addition, communities impose practices that are harmful to the bodies of women and girls, such as female genital mutilation (FGM), of which female circumcision is the most common form, that violate their physical integrity and have their origins in cultural, religious and social customs 2 . In West Africa, FGM is widely practised, although its prevalence varies between countries (see illustration below).

FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION/CUTTING (FGM/C)

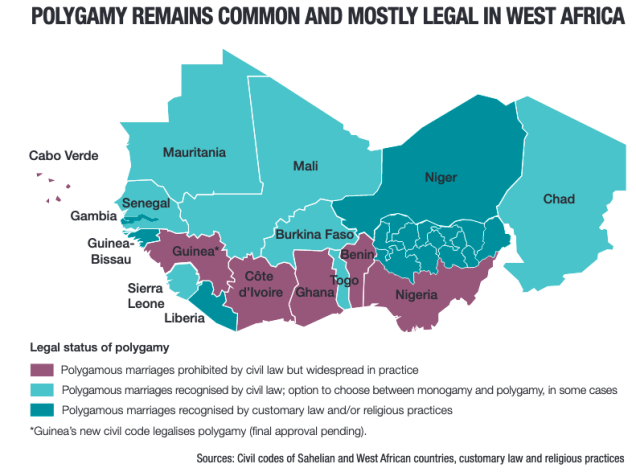

Furthermore, where customary law, religious practices and civic law are in agreement, the rights of women and girls are neglected and violated. This is particularly the case in all the countries in our study that legally allow polygamy, except for Niger. West Africa is the region where polygamy is most prevalent among the population: in Burkina Faso it is 36%, in Mali 34%, in Niger 29% and in Senegal 23% for the period 2010– 2018 [35] . In the DRC, polygamy is not widely practised, concerning only 2% of the population. The most common version of this practice is polygeny, where a man marries more than one wife, thus contributing to inequality between women and men.

In this context of widespread inequality and discrimination against women, including misogyny, male-controlled sexuality and social pressure on fertility, it is difficult for women and girls to access SRH care and information, to speak freely and confidently about their sexual and reproductive rights, and to claim these rights. SRH is also often considered to be a Western principle that is contrary to local values. The strength of these prejudices weighs particularly heavily on women and girls. However, gradual changes are taking place within more recent generations who are more able to demand their rights and have tools such as social media to inform themselves [36] .

Health systems in West and Central Africa

Numerous observations regarding the health system in these countries were made. The primary barriers between women and adolescent girls and SRH services are financial and geographical, especially for those living in rural areas, which range from 50% to over 70% depending on the country [37] . The presence of SRH services is uneven, with the peripheries being less equipped than the urban centres. Extending the national SRH programmes throughout the region is a real challenge, especially given the lack of resources and the instability of certain areas. The priorities are to strengthen health systems where they exist and ensure that good quality services are delivered.

The region’s health systems rely mainly on donations. Although countries committed in 2001 in the African Union’s Abuja Declaration to devote 15% of their national budgets to financing the health sector, 20% of which is dedicated to SRHR, this is still not the case for Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal and the DRC [38] . National resources allocated to health are insufficient to meet the demand, so people have to pay for care. The population’s expenditure on health is therefore low because of the significant cost that medical care represents [39] . In 2018, the Human Development Index (HDI) for the countries in our study was extremely low: Mali’s HDI was 0.422/1, Niger’s was 0.341/1, Senegal’s was 0.494/1, Burkina Faso’s is 0.434/1, and the DRC’s was 0.459/1. In Burkina Faso, a strong commitment was made by the government in September 2020 to provide free medical consultations, family planning services and contraceptives.

However, people are still confronted with discretionary decisions by health workers, especially in rural areas. In health centres, women and girls may be subject to the prejudices and moral representations of medical staff on SRH issues, which can interfere with diagnoses and care. Some refuse to prescribe or give access to a contraceptive method if the person is not married, considering that sexual relations outside of marriage are prohibited, whereas the law does not state anything of the sort. As Fatou Ndiaye Turpin, Executive Director of the Réseau Siggil Jigéen, reminds us, "the 2005 law on reproductive health recognizes that the right to reproductive health ‘is a fundamental and universal right guaranteed to every human being without discrimination on the basis of age, sex, wealth, religion, race, ethnicity, marital status or any other situation.’ There are no legal restrictions on young people’s access to contraception and other basic health services, such as pregnancy and STI testing, except for the requirement that they must be at least 15 years old to consent to HIV testing” [40] . The contraceptive prevalence rate remains a real challenge in a context in which sexuality outside marriage is still considered morally lax. The contraceptive needs of women aged fifteen to forty-nine are 58% satisfied in Burkina Faso, 56% in Senegal, 49% in Niger, 45% in Mali and 28% in DRC for the year 2021 [41] .

In other cases, medical care does not take into account women’s mental and physical suffering. As a result, there is a widespread lack of trust in health care workers [42] . This is particularly the case in Mali, where in hospitals « there is no pain treatment for women during childbirth: they lie on tables in a gynaecological position, in communal birthing rooms, with no consideration for their privacy or their physical and mental well-being; they cannot be accompanied in hospitals, so they give birth alone and sometimes they see each other die » [43] .

Girls’ education and schooling is a key element in the empowerment of girls and women. This gives them the ability to assert themselves, gain autonomy and make decisions about their bodies. Keeping girls in school helps prevent under-age pregnancies and gives them a future in which they gain skills to enter the labour market and contribute to the socio-economic development of the country [44] .

School is also the best place for young people to get information and advice on sexuality. Providing comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in schools is therefore crucial to raising awareness among young people. However, across the countries surveyed in our report, sexual and reproductive health education is widely perceived as encouraging young people to have sex. Because sexuality remains taboo and subject to prejudices within families and society, the subject is passed over in silence, contributing to the exposure of young people to many dangers, misinformation and the persistence of false beliefs. As a result, the contraceptive needs of 47% of unmarried Senegalese women aged fifteen to forty-nine year-old were not satisfied in 2017 [45] . In 2018, in Mali, this was the case for 52% of single women and girls [46] .

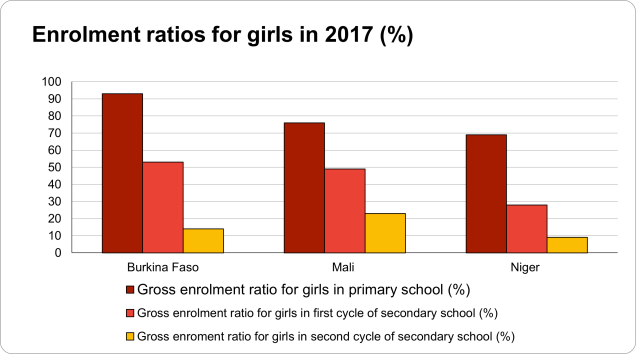

Parents know that their children have sex in their teens, and so to avoid the possibility of pregnancy out of wedlock, they encourage or even force their daughters to marry early and therefore leave school. The schooling of girls and information on SRH appear to be essential to ensure their emancipation and their ability to make choices informed by the knowledge of their rights. The marriage of girls goes results in them leaving school, which has immediate and long-term consequences for their physical and mental well-being and economic empowerment: they are separated from their families, exposed to sexual violence and dependent on their husbands. The table below shows the significant decline in girls’ attendance between junior high and high school, at which age they are often withdrawn from school to be married. This is confirmed by the low female literacy rate in the countries studied in this report: in 2018, more than 50% of women aged 15 and over were illiterate in region [47] .

Source: UNESCO database.

The impact of Covid-19 on SRHR in West and Central Africa

The economic consequences of the pandemic will be particularly felt in the region. According to the World Bank, sub-Saharan Africa will be the second most affected region after South Asia, with an estimated 34 million additional poor people in the region [48] . The conditions created by the Covid-19 health crisis have exacerbated the already alarming situation with regard to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, which have been deemed « non-essential ». They have thus been rendered invisible, with financial resources being mainly dedicated to governments’ priority concerns. The closure of SRH services, including those for mother and child health, has been due to cases of contamination in health care centres, a shortage of family planning resources particularly in rural areas, insufficient staff since they were reallocated to Covid-19 treatment units or abandoned their posts for fear of being contaminated, as well as loss of funding, which has been allocated to services dedicated to fighting Covid –19 [49] . On the population side, there was also a drop in attendance at the centres due to travel restrictions, fear of contracting the virus, lack of confidence in the health care system and reduced income due to the health crisis. Both the supply of and demand for SRH services have therefore been affected by the health crisis.

Furthermore, women and girls have been the first to suffer the consequences of the pandemic as social control over their bodies has been reinforced. The study carried out by Equipop on the consequences of Covid-19 on women’s rights and health in West Africa reveals that there is « a return of a certain moralistic and conservative attitude towards young people’s sexuality, characterized by promoting abstinence and making women feel guilty » [50] . This discourages women and girls, especially the younger ones, from going to health centres to receive health services or to seek information. In addition, women and girls who have been obtaining contraceptives in secret are at risk of facing the disapproval of their spouses or families if this becomes known. The breakdown of services and information on SRHR intensifies the vulnerable situation in which young people and women find themselves. In addition, with the closure of schools, curfews and lockdowns resulting in the confinement of women and men in their homes, gender-based violence, such as rape, female genital mutilation, forced marriages and child marriages, has seen an unprecedented increase. The testimonies gathered from local NGOs are unanimous on this subject: women and girls are suffering the full force of the negative consequences of the pandemic, which affect their freedom to control their own bodies.

According to the UN, « 47 million women could lose access to contraception, resulting in 7 million unwanted pregnancies » [51] . Furthermore, according to the UN’s April 2020 predictions, « an additional 31 million cases of gender-based violence can be expected to occur if lockdown continues for another six months” [52] . This is in addition to »13 million additional child marriages between 2020 and 2030 2030" and « 2 million cases of preventable female genital mutilation » over the next decade. The UN Women report published in September 2020 concluded that « decades of progress towards gender equality could be lost in one year of the pandemic » [53] .

Source: PAI, Mitigating the impacts of Covid-19 in low and middle income countries, 2020.

The pandemic has thus seriously undermined progress made in recent years in the field of SRHR. Civil society actors have responded by developing innovative strategies to continue their efforts.

C. ACTIONS BY LOCAL CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS, COMMUNITIES AND POLITICAL BODIES TO ADDRESS SRHR NEEDS IN THE REGION

In the face of legal, religious, societal, financial, security and geographical barriers to women’s and girls’ freedom to have full control over their bodies and to the provision of SRH services, local NGOs specialized in these areas are working to initiate and sustain positive change. Due to the nature of the SRHR field, NGOs adopt multi-sectoral approaches where access to education, social protection, health and law are intertwined in the implementation of their actions for the improvement of girls’ and women’s living conditions and the full exercise of their rights [54] .

Advocacy by local NGOs for governments

Their advocacy work with government institutions mainly calls for the establishment of a legal framework that protects women’s rights (including safe and legal abortion), as well as their physical and moral integrity with regard to SRH medical care, and that prohibits gender-based discrimination and violence. They work with parliamentarians and representatives of ministries responsible for health, education and women’s and girls’ issues to change the legal framework. This gives NGOs allies in government to take up their fight and support concrete legal progress in terms of SRHR . The main challenge is to achieve national ownership of SRHR issues. In the same perspective, NGOs demand that governments take up their responsibilities and commitments with regard to international and regional treaties upholding women’s rights that have been signed, with a view to respecting these rights and incorporating them into national legislation [55] . It is therefore essential for NGOs, governments and local political institutions to work together in order to « co-construct the response to SRHR needs on the ground and ensure the sustainability of projects by allowing local authorities to take over afterwards » [56] .

In some of the countries in our study, the government sometimes supports NGO projects. For example, in Niger, the National Assembly hosts the Nigerian Cell of Young Female Leaders (CNJFL) “Junior Parliament” project, which establishes a system of mentoring and leadership training between successful women and young girls at school [57] . In the DRC, the new government has almost 30% women. President Félix Tshisekedi spoke in favour of the promotion of women’s rights and mentioned the Maputo Protocol in his inaugural speech [58] . Furthermore, "the new government has put in place a programme of priority actions for the term of office, including family planning and the fight against gender-based violence. The Maputo Protocol is being implemented through a normative framework and a technical repository on women-centred comprehensive abortion care in the DRC. Thus, at the sub-region level, the DRC is progressively playing a leading role in SRHR, an influence that is reinforced by the presence of President Tshisekedi as the current chair of the African Union” [59] .

In Burkina Faso, champion of the “Bodily Autonomy and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights” action coalition within the framework of the Generation Equality Forum, the government stands out for its assertive and committed political discourse on SRHR. At the UN Commission on the Status of Women in 2021, the Minister of Health Charlemagne Ouédraogo reiterated Burkina Faso’s commitment to promote and guarantee women’s well-being and autonomy through free access to contraceptive and family planning services. He also made a progressive case for abortion and the importance of developing comprehensive sex education in schools to prepare future generations. The Minister of Health also emphasized the central role played by NGOs in governments’ strategies, saying that they should be responsible for monitoring the accountability of countries in terms of SRHR.

Advocacy by local NGOs for communities

Civil society organizations (CSOs) also carry out important advocacy work with communities through “community dialogue on SRHR to engage in discussions on the impacts of communities committing or not committing to the promotion of SRHR. These opportunities for interaction encourage intergenerational discussion, as well as discussions between women and men, i.e. groups that do not usually discuss sexual and reproductive health amongst themselves” [60] . When these NGOs reach out to communities, religious and community leaders are particularly targeted and made aware of the importance of women’s empowerment, girls’ education and the eradication of harmful practices such as FGM, underage and forced marriages. To do this, NGOs identify receptive leaders who will be listened to because of their influence and knowledge of the community, facilitating the transmission of information and the freeing of speech on certain sensitive SRHR issues. Indeed, "the voice of religious and community leaders matters so much that if they approve of something, the community accepts it. Religious leaders who are identified and won over to the cause then uphold the NGO’s discourse against child marriage, for example, and continue actions in the community after the NGO has left. They have the power to change behaviour within a community” [61] .

The strength of local NGOs lies in their ability to relay their awareness-raising message about SRHR through ambassadors in the communities, helping to create a network to fight misinformation and superstition. The intention is to engage all stakeholders in the community in order to provide them with the right information on SRHR and to include them in actions undertaken to promote SRHR. This strategy is all the more relevant as regular changes in political regimes disrupt any work carried out with political representatives. By engaging at the community level, continuity in NGO advocacy work is possible [62] .

Furthermore, "community ownership of SRHR is crucial as there are still zones where it is impossible to talk about SRHR and for it to be acknowledged that many adolescents are sexually active. Imams participate in many CSO networks and platforms at national and regional level and facilitate this advocacy work within communities and with the authorities. One example is the collaboration of the Ouagadougou partnership with the network of religious leaders in West Africa. There is a change in cultural acceptance of the right to contraception and medical abortion under certain conditions (rape, incest or danger to the mother). Progress is being made, albeit slowly. Moreover, the pressure and advocacy of youth movements is becoming so substantial that it cannot be ignored for long” [63] . The dynamism of young people’s demands for reliable information and access to SRHR services no longer allows communities to ignore these issues.

Thus, whether at the level of governments or civil society, progress is being made through a gradual opening of dialogue on SRHR. This must be continued and sustained. While « in the early 2010s, the subject of family planning was taboo, it is now being raised within the community and with policy makers » [64] . Advocacy by institutions such as the Ouagadougou Partnership, the African Union, the West African Health Organization and ECOWAS, is helping to revise national policies to incorporate new strategies for providing access to FP information and services to the entire population, including in hard-to-reach areas. Awareness of the importance of taking action on SRHR has thus been translated into action at regional, national and local levels. However, there are still many challenges in dealing with opposition and barriers to SRHR.

“Husband school" programmes implemented in all the countries studied aim to remove the barrier to information and access to sexual and reproductive health care. During these moments of exchange and awareness raising, men are involved and encouraged to acknowledge their responsibilities in issues relating to women’s rights, their autonomy and SRHR. Fertility concerns both men and women.

Although this may lead to an encouraging change in the acceptance of family planning discussions, as well as an increase in the number of women attending health centres [65] , the opinions of the women active in the NGOs interviewed [66] are nevertheless divided regarding the positive contribution of these programmes. While men are committed to addressing issues that were previously consciously passed over in silence, it gives them a platform where they can once again have the upper hand over women and their bodies. Indeed, in the countries surveyed, the majority of men control their partner’s sexuality, including the use of a method of contraception. However, it is primarily the responsibility of girls and women to freely make decisions that affect them. The Network of West African Young Feminists for Mali further argues that it is up to the whole population to « stop letting religious leaders and the government make decisions about SRHR so as not to allow a minority of men to mortgage young people’s futures » [67] .

Actions by local NGOs with and for youth

With regard to young people, NGOs are increasing their actions with and for them, which is a prerequisite for bringing about changes in mentalities and cultural and social practices, as well as for overturning old patterns in a region where people under the age of 25 represent more than 50% of the national population. Promoting female leadership and empowerment among young girls is a necessary condition for enabling new generations of women to make their own choices and express their needs in terms of SRHR. Their full emancipation depends on the realization of their potential, which must be communicated from the earliest age at school.

Among the actions carried out in schools to raise young people’s awareness of their SRHR and to open up dialogue on subjects considered taboo, the normalization of discussions about menstrual hygiene is for some NGOs, such as the CNJFL [68] , the keystone of their advocacy. In this sense, the CNJFL offers a safe space for discussion with young girls to fight against menstrual insecurity. Girls who menstruate are more likely to drop out of school because they cannot afford sanitary protection, because there are no separate latrines at school to give them privacy, and because the subject is taboo. Young boys are also involved through projects where they are trained in SRHR and girls’ empowerment issues and become 'ambassadors’. They are thus able to pass on this knowledge and become agents of change.

Providing comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in schools is another area where these NGOs work with young people. Despite a lack of consensus on the name of this programme and the community and religious tensions it provokes, it is essential to include CSE in the training curriculum of education provided. NGOs stress the importance of educating young people about SRH in order to give them the knowledge to make their own choices and protect them from harmful and dangerous practices, such as unprotected sex, female genital mutilation, underage marriage and pregnancy.

Getting girls into school and keeping them there are therefore key elements of NGO advocacy against child and forced marriages and against women’s and girls’ dependence on men for their livelihoods. Local associations try to explain to families and communities, through community debates, that a girl who receives a full education then has the possibility of obtaining economic independence, thereby enabling the family to avoid taking decisions against the physical and moral integrity of their daughters due to a lack of financial resources [69] .

In a context in which many local languages exist in West and Central African countries, language is another limitation to the dissemination of information on SRHR within communities. The transmission of information in rural areas where different languages are spoken has therefore required translation work by NGOs through intermediaries in order to bridge language-based knowledge gaps and to achieve community ownership of the information [70] .

To address the lack of information about SRHR and to promote its accessibility and understanding, NGOs are also using radio and social media to spread knowledge more widely. These methods have been intensified as a result of the health crisis. Civil society organizations active in the promotion and defence of SRHR within the countries studied have once again demonstrated their resilience. NGOs have redoubled their innovative strategies to ensure continuity of services and information for the population. Social media have been used to spread online health and telemedicine programmes. For example, women and girls were able to self-administer subcutaneous injections of DMPA, a pregnancy prevention method, through telephone monitoring [71] .

Whether smartphone applications, social media or radio are used, the goal remains the same: to address the barriers created by the health crisis so that women and girls can continue to receive care [72] . After the closure of schools, social media proved to be the ideal platform for maintaining communication and providing information and advice to young people. In addition, it enables widespread access to care and better dissemination of information on SRHR. For remote areas without Internet access, community relays and mobile teams have been strengthened to bridge the digital divide [73] .

2. FRANCE’S STRATEGY FOR OFFICIAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE FOR SRHR IN WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA

A. EVOLUTION OF THE INTEGRATION OF SRHR INTO FRENCH OFFICIAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE

To understand the changes in France’s official development assistance (ODA) policy regarding the integration of gender-related concepts, including SRHR, it is necessary to look at the first Stratégie genre et développement (Gender and Development Strategy) published by the government in 2007. In this document, France reports, for the first time, the adoption of a gender perspective in its external development assistance. Gender equality and women’s rights were included in France’s positions and programmes that it supports in international bodies, and access to SRH services was defined as an objective of France’s strategy. Following the evaluation of this document by the Observatoire de la parité entre les femmes et les hommes (Observatory of Parity between Women and Men) [74] , it was recommended that the government promote a cross-cutting approach [75] to gender issues in its development policies. To this end, « the training of agents, […] the provision of appropriate methodological tools and […] the reform of procedures for the appraisal, monitoring and evaluation of projects and programmes [76] » was recommended. The lack of resources and visibility is another element to be corrected.

In 2010, the French Muskoka Fund was established. Its mandate is to work towards the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) on reducing maternal and child mortality and increasing access to reproductive health care for nine countries in West and Central Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Chad and Togo). The French Muskoka Fund is an innovative coordination mechanism between the World Health Organization (WHO), UN Women, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to strengthen the health systems of these countries and implement programmes in the areas of maternal, newborn, child and adolescent reproductive health (RMNCAH). France is the founder and main donor of this fund and has pledged 500 million euros from 2011 to 2015 through multilateral and bilateral channels [77] . More recently, France has been funding these various organizations with €10 million per year under the French Muskoka Fund from 2017 to 2022, the year in which the fund is due to close [78] . In 2011, the Ouagadougou Partnership was added to this commitment by France, which participates through the French Development Agency (AFD), one of the partnership’s donors. Since 2020, the AFD has been financing projects in West Africa, Benin, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Senegal and Togo within the framework of the Ouagadougou Partnership [79] .

In 2014, under the five-year term of François Hollande, the Minister for Women’s Rights Najat Vallaud-Belkacem brought in the law no. 2014–873 in favour of real equality between women and men adopted on 4 August 2014. In the same year, the law n°2014–773 of 7 July on the orientation and programming of development and international solidarity policy gave a clear strategic direction to France’s development policies by including gender equality and considering gender as a cross-cutting issue in all sectors of French cooperation. This law affirms, among other things, the importance given to sexual and reproductive health by the French government. In the same year, the AFD adopted a cross-cutting intervention framework focused on gender and the reduction of gender inequalities, which takes a sectoral approach. The importance of « women’s and girls’ access to essential health information, commodities and services, with a focus on sexual health » [80] was thus highlighted.

Two years later, under Jean-Marc Ayrault’s government, a first report was devoted to SRHR in the document L’Action extérieure de la France sur les enjeux de population, de droits sexuels et reproductifs 2016–2020 proposed by Jean-Marc Ayrault, then Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Development, and André Vallini, Secretary of State in charge of Development and Francophonie. The three main areas are policy advocacy, reduction of harmful practices and family planning. This document is announced as a reference tool for French diplomacy, in which SRHR are seen as a key area of France’s political advocacy for gender equality and the defence of women’s rights. The approach of the government’s discourse was first to focus on the demographic dimension of SRHR and then to emphasize their importance for the empowerment of young women and equal opportunities between women and men. France’s role as a leading country within multilateral and regional bodies is underlined as a structuring axis of its political commitment to SRHR. In 2017, at the UN Commission on the Status of Women, the Minister for Families, Children and Women’s Rights, Laurence Rossignol, gave a speech committed to "the universal recognition of sexual and reproductive rights as an essential prerequisite for the empowerment of women” [81] . The renewal of this strategy for 2021–2024 is a crucial step in the government’s positioning on this issue and should enable it to strengthen its rights-based approach.

While France’s External Action on Population, Sexual and Reproductive Rights 2016–2020 presented the emergence of the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs’ knowledge of SRHR, the strategy currently being developed aims to address all SRHR-related issues and to demonstrate an evolving understanding of the whole SRHR “package”, by taking into account, in particular, menstrual hygiene and the fight against toxic masculinity, issues that have so far received little attention [82] . The progress observed and to come concerning SRHR is in line with that identified in public debate and supported by civil society in France and which influences international support for these subjects [83] .

In recent years, France’s commitment to gender equality has been strengthened under the presidency of Emmanuel Macron, who has made this issue « the major cause of his five-year term » [84] . French Official development assistance policy, the tool for implementing this priority, underwent a change in 2018 following the meeting of the Interministerial Committee for International Cooperation and Development [85] . It is stated that ODA pursues, among other things, the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through the identification of sectoral, budgetary and geographical indicators. Since then, gender equality has been considered as « a guiding and cross-cutting principle of France’s external action » [86] in which a rights-based approach is prioritized. ODA is also planned to reach 0.55% of gross national income (GNI) for the period 2018–2022. To achieve this, financial commitments have been made to UN Women, UNFPA and the French Muskoka Fund [87] . ODA funding for gender equality will be identified via the « gender marker » established by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) to ensure monitoring and accountability. In terms of geographical areas targeted by ODA, Africa is given particular attention, including the five countries in our study. Nevertheless, it should be stressed that the actions carried out in favour of SRH remain associated with objectives linked to demographic transition [88] , whereas the two approaches can be dissociated insofar as respect for individual rights is unconditional, independent of any public policy, health or demographic objective.

La Stratégie internationale de la France pour l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes (France’s International Strategy for Equality between Women and Men 2018–2022) advocates a rights-based approach to gender mainstreaming in all of France’s external action. The funding targets presented aim to achieve « 50% of programmable bilateral ODA, by volume of funding, with the primary or significant objective of reducing gender inequality by 2022 (OECD markers 1 and 2) » [89] . In addition, « the AFD will have an absolute value minimum volume target for funding programmes marked 2, according to a progressive trajectory that will aim for an amount of 700 million euros per year in 2022 » [90] .

Source: “Handbook on the OECD-DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker”, OECD, December 2016.

Shortly afterwards, France announced the adoption of feminist diplomacy as part of the new impetus given to the country’s ODA. Feminist diplomacy was previously upheld in 2016 by Pascale Boistard, Secretary of State for Women’s Rights, who made a declaration relating to professional equality, parity and women’s rights, arguing for the positive implications of implementing diplomacy promoting gender equality and women’s rights in societies [91] .

France’s feminist diplomacy As a new political concept, only four countries claim to uphold it, these include Sweden, Canada, France and Mexico. Feminist diplomacy in France was introduced by the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Europe, Jean-Yves Le Drian, on 8 March 2018. It is based on the principles of including gender equality in France’s foreign policy strategy, which includes combating gender inequality, defending women’s rights, mobilizing human and financial resources to achieve this and the involvement of more women actors in international relations.France’s feminist diplomacy is characterized as “pragmatic and progressive” by the High Council for Equality. While the approach is broad, priority themes have been identified: sexual and reproductive rights, combating sexual and gender-based violence, girls’ education and women’s economic empowerment. The implementation of the strategy is mainly carried out through official development assistance.

The draft programming law on solidarity development and the fight against global inequalities, proposed in March 2021, is part of the new feminist diplomacy. This bill stipulates that 20% of bilateral ODA commitments must have gender equality as a primary objective. In this way, the concepts of gender equality and respect for women’s rights are integrated in a cross-cutting manner into all of France’s programmes and interventions. This law replaces the law of 7 July 2014 and provides for an increase in ODA to 0.55% of GNI by 2022 and then to 0.7% of GNI in 2025. The sub-Saharan African region is particularly concerned by this ODA review. Indeed, it is stated that the AFD « is placing increasing emphasis on the SRHR approach, the fight against female genital mutilation and population dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa » [92] .

In the context of these various initiatives to promote gender equality in France’s external actions, ambassadors are key actors in the implementation of the government’s commitments and upholding the country’s discourse on rights and SRH issues. In order for foreign policy to reflect the commitments made by the government, ambassadors must promote and highlight the issues defined with the governments of their countries of residence, while taking into account their sensitivities in order to maintain an open dialogue and gradually make progress.

Following the Generation Equality Forum, which will close in early July 2021, the French Embassy will continue to « accompany and support initiatives taken on these themes with the aim of contributing to the mobilization of new funding to carry out Burkina Faso’s commitments made at the Generation Equality Forum », in conjunction with UN Women, which is at the forefront of the defence of women and girls with governments and civil society. In this regard, "Burkina Faso should benefit from additional funding from 2021 thanks to its return to the French Muskoka Fund, which aims to improve the health of women, newborns, children and adolescents in West and Central Africa” [93] .

On the international scene, France has asserted its willingness to uphold strong, committed political advocacy for gender equality and women’s right to have control over their own bodies. However, for several years, the international environment has been marked by a resurgence of conservatism and traditionalism championed in international bodies by a coalition of countries such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, Brazil and, more recently, by the United States under the presidency of Donald Trump, leading to a regression (or backlash) in women’s rights throughout the world [94] . The former US President waged a war on women’s rights, including SRHR, in multilateral bodies. In 2017, the Mexico City Policy, also known as the “global gag rule”, was reinstated by Donald Trump. « This rule prohibits the allocation of US federal funds to civil society organizations working abroad that provide abortion counselling or referrals, advocate for the decriminalization of voluntary termination of pregnancy, or expand available abortion services – even when the US does not fund these services itself” [95] . The consequences of this measure have been disastrous for funding for the health sector and for official development assistance dedicated to SRHR, resulting in considerable financial losses for SRH services. Following the US announcement, it was estimated that the NGOs concerned would suffer losses of $600 million [96] . To address this, a fund-raising campaign, She Decides , was launched in 2017. France announced its support by committing an additional €1.5 million to UNFPA and in 2018 the French government announced that it would »allocate an additional €10 million for SRHR concurrent with the 62nd session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women” [97] .

In April 2019, the US refused to vote for a UN resolution against sexual violence in armed conflict on the grounds that mentioning sexual and reproductive health was tantamount to supporting abortion [98] . Finally, in October 2020, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo used the country’s influence to encourage around 30 governments to sign the Geneva Consensus Declaration [99] , which states that abortion is a matter of national law and not of international jurisdiction. The election of Joe Biden as President of the United States in 2021 was an opportunity to lift all of these measures attacking women’s rights.

In the face of increasing advocacy and heavy-handed decision-making by conservative and religious groups around the world, France has decided to react and intensify its advocacy on SRHR 3 at the UN Human Rights Council, the G7, the UN Commission on Population and Development, the UN General Assembly and the UN Commission on the Status of Women. In the mid-term accountability report on France’s External Action on Population, Sexual and Reproductive Rights 2016–2020, it mentions France’s initiative to draft “a communiqué endorsed by thirty-one UN Member States that regretted the failure of the negotiations and called for the recognition of sexual and reproductive rights, including voluntary termination of pregnancy, as full human rights” [100] .

The Generation Equality Forum, co-chaired by the French government, is an opportunity to create an action coalition committed to the defence of SRHR through the collaboration of multiple actors, such as governments, NGOs and companies. This configuration makes it possible to bypass the usual blockages that prevail within multilateral bodies with regard to women’s rights and in particular the issue of SRHR. It is also an opportunity to create synergy across the world in favour of the implementation of concrete initiatives for SRHR through dedicated funding over five years.

The Generation Equality Forum The Generation Equality Forum is organized by UN Women and co-chaired by France and Mexico.It is a global gathering for gender equality that puts civil society and all stakeholders at the heart of its actions. The forum is essentially in line with the same logic that made possible [twenty-six years ago] the decisive step forward represented by the adoption of the Beijing Platform for Action. This programme and its progress embody the power of activism, feminist solidarity and youth leadership to achieve truly transformative change in our societies.The Generation Equality Forum is a high point for the commitment of gender equality advocates from every sector of society (governments, civil society, the private sector, entrepreneurs, trade unions, artists, academics and influencers), which will initiate a global public debate on the need for urgent action and accountability for gender equality for all actors.(Source: https ://forum.generationequality.org/)

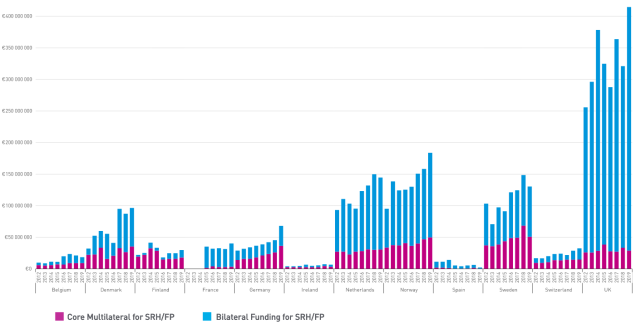

B. FRANCE’S FUNDING FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS

The implementation of these multiple commitments and initiatives defined by France in favour of the defence of women’s rights and SRHR requires the allocation of funds. So, what is the current situation regarding France’s official development assistance (ODA) funding for SRHR in sub-Saharan Africa? The funding dedicated to SRHR by the French government will be presented in the most comprehensive but not exhaustive manner possible, due to the difficulty of tracing and identifying these funds.

Indeed, the report presented by the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs in France’s International Strategy for Equality between Women and Men (2018–2022) notes the difficulty of summarizing all ODA data. The data is public, but the SRHR programmes, as we have seen, are cross-cutting, and can therefore be counted across different programmes, whether they concern health, education or the fight against discrimination. In addition, programme monitoring indicators are analytical in nature, whereas SRHR follow multiple objectives, which can therefore be counted several times.

This is compounded by the diversity of methodologies used to account for French ODA funding for SRHR. There is therefore a lack of precision in identifying and accounting for such funding. In addition, the diversity of accounting methodologies does not enable the comparison of figures corresponding to French ODA allocated to SRHR.

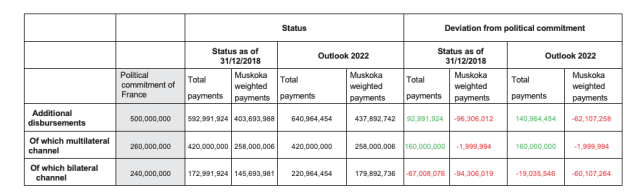

There can be no doubt that these technical difficulties in monitoring the programmes limit their understanding for external observers, partners in public action and, even more so, for citizens. In terms of accountability, it would be necessary to define a method, shared with all stakeholders (ministries, operators, associations, civil society, etc.) to cross-check information and provide assessments to verify that aid programmes are in line with the commitments made by France on the international scene, particularly when it acts as a champion for a major cause. The lack of visibility is indeed « a major challenge for the understanding and legitimacy of development, cooperation policies, and for enhancing aid effectiveness » [101] . In 2016, Family Planning, Equipop and Médecins du Monde published a joint position paper [102] about French funding for SRHR where they agreed that precise identification of such funding is complex. In 2020, the French Development Agency (AFD), in its evaluation of the French Muskoka commitment, demonstrated that "the heterogeneity of the purposes of the accountability periods, collection procedures and the indicators” [103] makes it difficult to analyse funding associated with this issue.

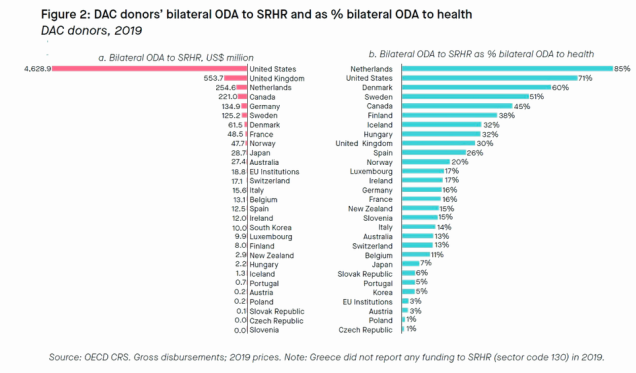

Methodologies for accounting for financial resources allocated to SRHR by France