Decoupling electricity and gas prices: mission impossible?

Since the beginning of the energy crisis, there have been numerous proposals to separate electricity prices from gas prices. According to Nicolas Goldberg and Antoine Guillou, the time has to correctly identify the problems and correct them rather than constantly looking backwards. The first problem is that wholesale markets are doing what they are designed to do (ensure the balance between production and consumption at a time t) but they are not sending the right investment signals. The second problem is that retail markets pass the volatility of wholesale prices on to the final consumer, when they should be protecting them against this volatility. To correct these failures, operators must be given more visibility via « contracts for difference », long-term contracts (PPAs) must be generalized and much more demanding regulation must be put in place for suppliers in retail markets with prudent investor rules to be respected in the same way as for banks.

The current energy crisis once again highlights Europe’s massive dependence on imported fossil fuels. The war in Ukraine illustrates the vulnerability of European economies to geopolitical tensions and their consequences on the price of oil and gas, which are overwhelmingly imported from other regions of the world. To the dismay of businesses and households, energy prices have reached extremely high levels in recent months and electricity has not been spared. In the electricity sector, these difficulties are not only linked to the current economic environment: while the European Union has set itself the ambition, through its Green Deal, to free itself from fossil fuels and significantly reduce its CO2 emissions (-55% by 2030) and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 while preserving its economic competitiveness, the rate of investment needed in the production of decarbonized electricity has clearly been insufficient for years, given that electricity should be taking an increasing place in our energy mix.

The current crisis thus illustrates both the strengths (solidarity and coordination between countries, balancing the network at the best cost at any given time) and weaknesses (lack of long-term signals and consequently insufficient investment, exposure of end consumers to price volatility, particularly of fossil fuels) of the European electricity markets, which were created with the easing of restrictions on the sector in the 1990s and have undergone numerous changes since then.

Major reform is now urgently needed, but care must be taken not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. The European wholesale electricity markets now allow for an efficient real-time balance between production and consumption, which is essential because electricity cannot be directly stored. This optimisation has been made possible by the multiplication of electricity interconnections in Europe and the establishment of a common electricity market, in which the means of production used are always the least expensive among those available at a given time (also taking into account the price of CO2). In theory, this system should largely benefit the end consumer. However, these wholesale markets suffer from myopia: they do not provide sufficient visibility on future prices. Therefore, they do not guide towards long-term investments, which may lead, in the absence of any public intervention, to a risk of shortages. Worse, as the current crisis cruelly highlights, end consumers find themselves unwillingly exposed to the volatility of wholesale market prices, and therefore very often to the price of imported fossil gas, because of a retail market that is insufficiently regulated (no obligation to cover volumes sold), sometimes failing (bankruptcy of suppliers who have not covered themselves, abandonment of customers, etc.) and pursuing the wrong objectives, such as passing on instantaneous electricity prices to the end customer instead of tariff stability.

Many false solutions have been put forward recently and seem to us to be counterproductive (such as the « Iberian exception », which we look at later, or the removal of a supposed « administrative rule obliging the price of electricity to be indexed to that of gas »), or even dangerous (such as a straightforward exit from the European market).

Given that the situation is no longer tenable for our industries, EU countries and consumers at every level, we propose two categories of measures to enable us to reinvest in our means of low-carbon electricity production and to protect end consumers from market volatility, mainly due to the volatility of fossil fuel prices:

- For the European wholesale electricity markets:

- Introduce a reform that reconciles investment planning with short-term optimization of the electricity system. To do this, extend the system of « contracts for difference » (CfD) already in force for renewable energies to all existing and future decarbonized production (based on the respect of CO2 emissions criteria), with a relaxation of the rules allowing long-term contracts to be proposed* (generally called Power Purchase Agreements or PPAs).

- Extend the visibility of wholesale markets beyond three years.

- Strengthen the coordination of national planning on electricity production.

- Set European supply security targets, enabling remuneration of means of decarbonized flexibility in a harmonized framework.

- In the retail market, on which the majority of end consumers depend, there is a need to strengthen regulation by introducing a system of prudent investment rules for electricity suppliers:

- Regular checks by national regulators on the coverage of suppliers’ portfolios, to be assessed in relation to their available assets. These hedges for suppliers could be ensured by long-term contracts (PPAs), sufficient dedicated cash flow, and their own means of production, possibly covered by public support, the objective being for only a certain percentage of short-term wholesale prices to impact customers’ bills. Regular stress tests could be carried out to assess the ability of suppliers to withstand a sudden change in market prices and avoid the cascading defaults or harmful effects of wholesale market volatility on end consumers that we have seen this year. Progressive sanctions or even withdrawal of supply licences could be envisaged for non-compliance with these hedging standards.

- The reform of the supplier of last resort system, the financing of which should be shared between all suppliers (like an insurance policy, because that is effectively what it is).

- Relaxation of the rules on long-term contracts for direct consumers (in particular allowing high-consumption business customers to commit themselves for more than three years) or groupings of suppliers to supply to end customers. These long-term contracts, together with the above-mentioned prudent investment rules limiting speculation, should allow consumers to benefit from these long-term prices rather than being exposed to the vagaries of the market.

The combination of these two families of proposals on the wholesale and retail markets would make it possible both to stimulate the investments needed for climate transition and the security of Europe’s supply, and to ensure that consumers’ bills are more closely linked to European production and decreasingly to the geopolitical ups and downs to which fossil fuels are subject.

*Long-term contracts allow an agreement between a producer and a consumer (either directly or through an energy supplier) over a long period of time (usually 10 years or more) to guarantee a quantity delivered at a contractually agreed price, thus enabling visibility on prices and volumes delivered.

| This is the English version of a text published in January on Terra Nova website |

Introduction

Twenty-five years after the first directive to construct a harmonized European electricity market, the wholesale electricity markets have reached relative maturity. They are physically and economically interconnected in the various European countries thanks to two components: the development of electricity transmission networks, allowing for ever greater physical interconnection between the national electricity networks, and the gradual construction of the European electricity market, in particular through electricity exchange mechanisms. The latter are marketplaces in which various players can buy or sell quantities of electricity, regardless of its origin, thus enabling economic optimisation of electricity production resources on a European scale to guarantee the balance between production and consumption at any given time.

However, these wholesale markets are now in turmoil because of the excessive prices that arise within them and the volatility to which consumers are then exposed in the retail market (on which the vast majority of consumers depend, who do not buy directly via the wholesale markets, but take out a contract with a supplier, who in turn buys on the wholesale market). Since mid-2021, prices on European wholesale markets have reached very high levels for several reasons, which led several European countries to introduce measures to limit increased bills for consumers in the autumn of 2021. Faced with this energy turmoil and its consequences, it would be tempting to ignore the message sent by these wholesale markets, and to bury one’s head in the sand, rather than acknowledging the threefold problem from which the European Union suffers in this area: an over-dependence on fossil gas to balance its electricity network, under-investment in electricity production due to the short-sightedness of the wholesale markets and a retail market that is insufficiently regulated (no obligation to cover the volumes sold), sometimes failing (bankruptcy of suppliers who have not covered themselves, abandonment of customers, etc.) and pursuing the wrong objectives, such as that of passing on short-term electricity prices to the end customer[1]. Tensions over gas supplies and then the war in Ukraine did not in themselves cause these weaknesses: they simply revealed them. If the war were to end tomorrow, our electricity market would still suffer from the same design flaws with an over-reliance on imported energy, especially fossil gas, for grid balancing and under-investment in electricity generation capacity. It is precisely these shortcomings that need to be corrected in order to balance the electricity grid in a sustainable way, through investing to preserve the climate and protect consumers.

Contrary to what some economic and political actors claim, simply exiting the European electricity market would be counterproductive, and even dangerous, as it has proven to be an indispensable resilience factor in case of crisis and its operation sends the right signal to balance the electricity grid at any given time. Since electricity cannot be stored (or only to a limited extent, in other forms), production must always be equal to consumption for the European electricity grid. The European electricity markets are structured in such a way that the least expensive means of production available throughout Europe at any given time are used as a priority to ensure this balance, with solidarity mechanisms between countries, which are very useful for the EU’s importing countries, such as France exceptionally this winter, and for other countries such as Italy or any other country which can benefit from European solidarity in this way to avoid electricity supply malfunctions. However, while this market does allow for short-term equilibrium at the best price, it does not send a sufficiently robust signal in the long term to trigger investments, leading to under-investment in energy transition and putting the objectives of the European Green Deal at risk.

Furthermore, the functioning of the retail market, which is supposed to act as an intermediary between the wholesale market and final consumers, overexposes consumers to the variations of the wholesale markets. Suppliers should have a diversified, long-term procurement strategy. However, they are too dependent on variations in the wholesale market that supplies them, often with no alternative to obtain the volumes they require, and are therefore too vulnerable to price peaks caused by sudden variations in the price of imported fossil fuels, which they pass on to their customers instead of cushioning them through sufficient long-term hedging. The repercussions of these high prices on end consumers are extremely problematic with increased fuel poverty, factory closures, obstacles to relocation, and impacts on countries’ budgets, which are obliged to adopt costly tariff shields, etc. So how can the right investment signals be created while avoiding exposing end customers, whether industrial or private, to price volatility, which is not unusual for the wholesale market but difficult to manage for the retail market? How can we best decouple electricity prices from fossil gas prices?

In the face of soaring and volatile wholesale electricity markets, the retail market has revealed many weaknesses

As gas prices began to increase significantly (even before the war in Ukraine started, due to the combined effects of reduced gas flows from Russia from mid-2021, higher CO2 prices and the post-COVID global economic recovery), various economic and political actors declared that it was not normal for prices to be based solely on those of gas when there are other means of electricity generation in Europe that should be used to set the level of prices charged to consumers.

Behind this statement lies a frequent confusion between two electricity markets: on the one hand, the wholesale market (characterized by electricity exchange mechanisms), which does indeed vary in near-real time depending on numerous factors (including, but not limited to, the price of gas); and on the other hand, the retail market (consumers signing a supply contract with a supplier), which would indeed not be so volatile if it were properly regulated with real consumer protection objectives. To clarify this, let’s take a closer look at the role of each of these two markets.

In the wholesale markets and the electricity exchanges, several products coexist: it is possible to buy electricity for an hour, a day, a week, a month or even for periods of up to a year. The prices of short-term products, such as those for one hour or for the next day, vary strongly and continuously to reflect the physical and economic state of the electricity system, which depends on several parameters: temperature, wind power, sunshine, state of production facilities, price of fossil fuels, cost of carbon, stocks, etc. It is possible to buy forward products on this wholesale market, i.e. to buy quantities of electricity up to three years before the delivery date: these products follow the trends of short-term products because they are based on price expectations that should enable economic players to hedge against shorter-term variations. These variations are normal and even necessary to ensure that the electricity system is balanced at all times, as electricity is not a directly storable commodity. This operation and this diversity of products allow two things: to have a short-term price signal to reflect the cost of balancing electricity production and consumption (an essential balance to ensure that there are no outages due to an imbalance) and protection against excessive variations from one day to the next via forward products, thanks to which a player in the wholesale market can buy the same quantity of electricity over a longer period, of up to three years, to avoid having to buy it every day and thus protect itself from price variations on the bulk of its supply

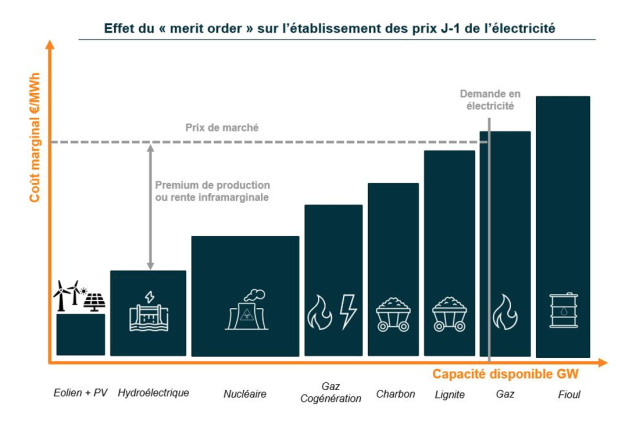

In these wholesale markets, the day-ahead prices are positioned according to the last power plant called, ensuring that its costs will be covered and thus balancing the electricity grid. As electricity cannot be stored directly, production must be equal to consumption at all times: this is the balance required for the electricity grid. To do this, any power plant whose production is needed to ensure balance must be guaranteed that it will cover its operating costs, including the most expensive power plant needed at any time t, otherwise the balance would fail and the grid would collapse. Therefore, all power plants in operation from one day to the next are remunerated at the price of the most expensive power plant needed to balance the grid at that time. Contrary to popular belief, this operation allows the overall cost of balancing the network to be brought down and priority to be given to resources with low operating costs. With this system (known as marginal pricing, i.e. with the highest price selected), each producer is incentivized to position themselves with the lowest possible selling price (generally based on its operating costs) because what counts is that it is « called » to operate and receives the marginal price, rather than offering the highest possible price and risk not being called. This defines the « merit order » for the electricity market: it means that the means of production are called in order of increasing marginal costs. In other words, this system starts by calling on the means of production with the lowest usage costs and ends with those with the highest usage costs, including the costs linked to the European market for CO2 emission quotas (issued on the « EU-ETS » market) which favours the least carbon-intensive means of production (renewable, nuclear, etc.) and penalizes the others (fossil gas, coal, fuel oil, etc.).

Payment at the marginal price thereby generates an "inframarginal rent” for suppliers other than the last power plant called, which is simply the profit resulting from the difference between their operating cost and the market price at time t (see diagram below). This raises the issue of the management and use of this inframarginal rent, which we will address later. It should be noted that more decarbonized production in the electricity mix would make the occasions when it was necessary to resort to fossil gas less frequent, thereby reducing the impact of its price on the wholesale market price of electricity; this is why it is important to invest in local, low-carbon production.

Wholesale market marginal pricing structure: each means of production called before gas receives a production premium: this is the inframarginal rent

In a desirable market operation, final consumers (private or industrial) would not be subject to the sudden variations of the wholesale market, because they obtain their electricity via the secondary, retail market through the intermediary of their energy supplier. In this retail market, it is the energy supplier who is supposed to buy the energy needed to supply its customers at all times, thanks to a diversified supply strategy, so that the end customer is not charged the spot market cost (i.e. the price of the day in the electricity marketplace, which can vary greatly from one day to the next), but rather the average price of electricity smoothed over a longer period. Some consumers, usually those who consume a significant volume, intentionally expose themselves to spot prices, but this is then a deliberate economic choice in their purchasing strategy and they have to accept the associated risks. However, it is important not to mix everything up: contrary to what some politicians have claimed, French consumers do not pay the marginal cost of electricity for administrative reasons. It is the way the wholesale market operates (not the retail market) that enables the electricity grid to be balanced, and which is not passed on in full to the bills of retail consumers. What the final consumer pays on the retail market is a weighted price of electricity in which the cost of short-term equilibrium is one component among others (or is the result of a deliberate economic choice for some consumers, as mentioned above). In addition to taxes and the cost of the grid, a consumer’s electricity bill should certainly contain some of the cost of balancing the grid (but we believe to a lesser extent than it currently does), and most importantly, in theory, it should contain a large proportion of longer-term supplies, so that the consumer benefits, at least in part, from the real average cost of the electricity system. This is already partly the case in some countries, such as France, via a regulated nuclear share that all consumers have in their bills.

In the current crisis, the wholesale markets have sent a signal of high balancing costs due to soaring gas prices and supply difficulties in some EU countries. Under these various pressures, the retail market has revealed the extent of its shortcomings, which were already widely known, but until now had remained relatively inconsequential as long as the wholesale market price was low:

- A number of suppliers went bankrupt because they did not have sufficient hedges to cope with the situation: either they had counted on prices falling or they did not have the cash flow to support the price rise or the risk to which it exposed them. The bankruptcies of these suppliers who gambled recklessly with the risk involved meant their customers had to urgently find new suppliers who could only offer them very disadvantageous prices given the need to supply them immediately in a rising market[2]. This exposure to market risk and the need for cash flow or hedging for electricity suppliers is thus reminiscent of the banking crisis. Unlike the former, however, banks are subject to the Basel III regulations and must be able to pass a certain number of stress tests to ensure that they do not take too much risk with their customers’ deposits.

- Some suppliers who were properly covered nevertheless abused the system by deliberately separating themselves from their end customers (suspension of offers, non-renewal of contracts, announcements of sometimes abusive price increases, etc.) in order to be able to resell the energy they had bought in advance on the markets and pocket the surplus value. Their abandoned customers had to join a last resort supplier, which then had to buy the energy needed to supply these new customers at a high price (a situation it could not have anticipated).

- Contract renewals have left customers highly exposed to variations in wholesale market prices, with suppliers sourcing most of their supplies from this wholesale market, with no long-term hedging for member countries without this type of regulation.-

More than how the wholesale markets operate, it is primarily this lack of regulation of the retail market, whose objectives need to be reviewed, which leads to unacceptable situations with consumers exposed to the volatility of wholesale market prices, accompanied by requests for intervention by the public authorities. This conclusion leads us to a series of proposals: we need reforms in retail markets to ensure that consumers are protected against the failures or abuses of poorly managed or unscrupulous suppliers. Furthermore, it must be possible to avoid suppliers only sourcing from a wholesale market whose prices are strongly coupled to the balancing price, which is itself very often influenced by the price of imported fossil gas. This will require, among other things, the possibility of long-term contracts (PPAs) offering different pricing from the balancing price, as well as the possibility of longer-term commitment with the supplier.

Wholesale electricity markets give no investment signal and end up generating a risk of shortage

The major failures of the retail market do not, however, exempt the European wholesale markets from criticism. The latter are short-sighted: they only take into account the short term. Currently, it is only possible to have price visibility for a maximum of three years. However, any means of electricity generation takes more than three years to be deployed. It is therefore impossible for a project developer to know at what price it will be able to sell its electricity and over what timeframe it will be able to cover its investment costs, which is an important factor given that installations generally have a life of at least 20 or 30 years. All means of production are thus confronted with the uncertainty of market prices, so much so that hardly any means of electricity production is developed today without bypassing the market and relying on state support, generally through direct public funding or a commitment on the buy-back price of the electricity to be produced. The market alone is therefore not an incentive to invest in new electricity capacity, as prices are so volatile and only valid in the short term; this is an issue that we have long highlighted[3].

Worse still, the European Commission, on the basis of the economic theory behind the creation of the market in the 1990s, has historically aimed to discourage the development of any long-term gas and electricity contracts. Such contracts were considered to be an obstacle to competition and the optimal functioning of the market. For example, any contract longer than four years is now subject to an investigation to ensure that it does not constitute such an obstacle. As a result, long-term commitment contracts, such as Exeltium[4] in France, which were developed without state support, took more than five years to set up because of the necessary investigations, even though the volumes involved were relatively small. As an illustration of the contradictions generated by this type of market operation, the European Union, with the approval of the Member States, sets the latter renewable energy production targets, while at the same time maintaining that each country in the Union remains free to determine the direction of its energy mix. However, as the market alone does not make it possible to achieve these objectives, the Commission has developed rules for circumventing the market (in particular through guidelines on state aid) in order to provide a framework for the implementation of palliatives[5] to the shortcomings of the market that the EU has itself created!

The theory behind the liberalisation of the 1990s that the link between the retail and wholesale markets through suppliers would be sufficient to give the right investment signals has been thoroughly undermined. Moreover, the objectives pursued during that period, such as optimising a system that was then oversized and amortised, are no longer those of today, namely the urgent need to respond to the climate crisis and the necessary investment to overcome the energy shortage.

Faced with these contradictory objectives, the time has come for clarification:

- Targets in terms of the energy mix are indeed a matter of Community law and Member States must at least accept some kind of coordination within the framework of the Union, with converging objectives and shared security of supply criteria[6].

- Public incentives must be allowed to play a full role in guiding long-term investment in additional decarbonized production. The market alone does not enable reaction to signs of scarcity which we must be able to avoid. Only strong public support and long-term contracts (PPAs) will enable Member States to accelerate their energy transition and the European Union to free itself from its dependence on fossil fuels, which the current crisis has once again highlighted.

- In this context, long-term contracts (private PPAs or via public support schemes) should not be seen as a hindrance to the proper functioning of the market, but as a tool to encourage investment and protect end-users from excessive volatility, while at the same time short-term markets can continue to exist to enable the balancing of the grid at the best cost. These long-term contracts could also be accompanied by monitoring and data transparency mechanisms to avoid excessive price divergences in the downstream market.

Faced with this situation, the European Union is at a crossroads: continuing with the model put in place in the 1990s, based on the theory that the link between the retail and wholesale markets should make it possible to give the right investment signals, would require major strengthening of the retail market regulations – which is necessary in any case – but there is no guarantee that this would be enough. The alternative we propose in this paper is to implement new regulations, adapted to the public objectives of developing decarbonized energies and securing the supply, in which all consumers would pay the average cost of electricity, but with effective protection from the volatility of prices on the wholesale market.

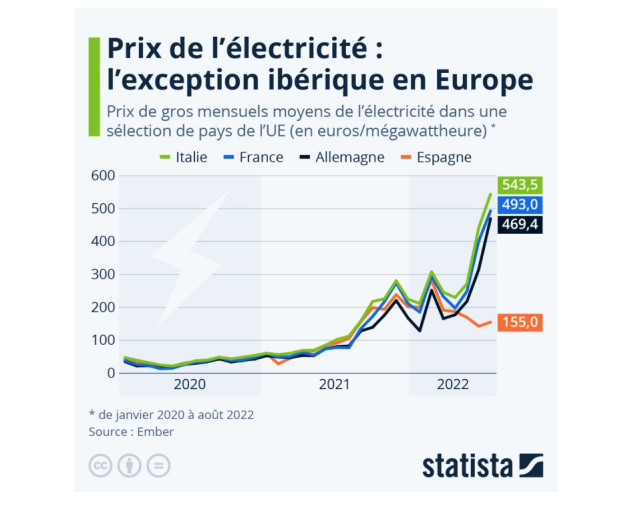

The Iberian exception: a flawed idea Faced with soaring prices, several countries have taken measures to protect their consumers. Among them, Spain and Portugal obtained the right from the Commission to temporarily cap the prices of gas-fired electricity: this is what has become known as the Iberian exception. Because of this cap, wholesale prices in the Iberian Peninsula do not move above a certain price. Its apparent success compared to the rest of Europe has given rise in recent months to several misconceptions about this system, which many describe as a panacea and would like to copy. However, it is necessary to analyse the functioning of such a mechanism to understand that it is no more protective than traditional tariff shields and that it also has several side effects that should be avoided. Firstly, contrary to what is sometimes claimed, Spain and Portugal did not « leave the market », nor did they « twist the European Commission’s arm ». These two countries are still integrated into the European market and the Commission has only authorized the capping of prices for electricity produced from gas, on condition that the cost of this system is passed on to the consumer to avoid any distortion of competition. In this way, Iberian consumers do pay the real cost of balancing, but through a tax on their bills, whose level is determined by gas prices, rather than a market price. The only effect produced concerns the « infra-marginal rent » of the means of non-gas production mentioned above: this rent is lowered by this system since the last power station called sets a capped price. Note, however, that the reduction of this rent can be achieved by many other systems, which have already been put in place elsewhere in Europe and more particularly in France (Contracts for Difference[7], taxation of excess profits, etc.). The effect on an electricity bill is thus small (around 10% – 15%) given that consumers must now pay a tax that depends on gas prices. Secondly, this system generates « leakage », as the Iberian Peninsula is connected to France. The latter can import electricity at a much lower price because it is subsidised by Spanish consumers. If a more interconnected country, such as France or Germany for example, had adopted such a mechanism (and other countries had not), the leakage would have been even greater. Furthermore, it should be remembered that when a country is a net importer of electricity, the marginal power plant setting the price is located outside its borders. Subsidising the production of electricity from domestic gas-fired power stations would thus have no effect on the marginal price: the effect would just be to call the French gas-fired power stations before those within the borders which would have set the marginal price, thus de-optimising the balancing price to the detriment of consumers. Finally, to this must be added the fact that the Iberian system invites the burning of more gas by forcing its use to produce electricity rather than by activating other means of storage (load shedding, hydraulics, imports, etc.), which is precisely the opposite of what should be done at this time. Indeed, in the midst of the gas crisis, the last six months of 2022 saw an increase in the use of gas-fired power plants in Spain of more than 40% compared to the same period in 2021, despite the increase in renewable energy production and a decrease in consumption[8]. The pitfalls of this system are numerous and, in order to be applied to other countries, it would be necessary for all European countries to adopt this system, with redistributive effects to be quantified (and paid for by a European fund that would have had to be supplied using a method that would itself have had to be determined), a counterproductive over-utilisation of gas-fired power stations, and potential leaks in countries neighbouring the European Union (United Kingdom, Switzerland, Bosnia, Serbia, etc.). The effect would have been clearly visible on wholesale prices but with a less immediate benefit for consumers with a redistribution of excess profits via taxation as decided by the European Union. This analysis leads us to conclude that widespread adoption of the « Iberian exception » should be ruled out. |

In the wholesale markets, Spain’s prices are heavily capped, in sharp contrast to other countries. However, Spanish consumers do not necessarily benefit at the retail level, as they have to pay a tax to cap this price, as shown in the Spanish invoice below.

On an electricity bill, Spanish consumers pay a tax, in this case called the « Mecanismo de ajuste del Real Decreto-ley », amounting to about 130 €/MWh, which can change according to gas prices. Consumers thus pay the real market price, but in a different form.

A new regulation to reconcile adequate investment signals, capture of excess profits and consumer protection

Faced with the current situation, and under pressure from member countries, the European Commission has announced a mechanism to reduce the excess profits of electricity producers with the capture of revenues from the sale of electricity above 180€/MWh. This measure would make it possible to capture the infra-marginal rent of production facilities which, thanks to a windfall effect linked to the surge in gas prices, are able to sell their electricity at a marginal price much higher than their production costs and thus reap excess profits. This tax would thus make it possible to maintain the short-term signals of the wholesale market while avoiding the excess profits induced by the insufficient proportion of long-term contracts in the market, leading to the surge in market prices being passed on to the final consumer.

However, this mechanism is too timid and is only intended to be temporary: at €180/MWh, this revenue cap is too high. It should be remembered that the member countries’ tariff shields began to be implemented in autumn 2021 as soon as prices reached €85/MWh on the wholesale markets, which had been around €50/MWh in recent years. It should also be noted that France wanted to lower the revenue cap proposed by the European Commission for electricity producers to €100/MWh rather than €180/MWh, which seems to be more balanced with regard to the costs of the production facilities.

However, in order to have a better sharing of risks between producers and consumers, the European mechanism lacks a revenue floor to secure producers against a future market downturn. Indeed, if the revenues of electricity producers are capped to avoid excess profits when market prices are high, it would seem fair and logical that producers are in turn protected with a revenue floor against falls in market prices that would lead to heavy losses for them, as was the case between 2015 and 2018. In addition to a revenue cap, there should be a revenue floor to ensure that electricity producers are able to cover their costs and thus maintain a sufficient incentive to make the investments in decarbonized electricity production that we need. The income obtained by the producer would thus fluctuate between a price floor and a price cap: above the cap, the income would be taxed, and below the floor, the State would subsidize the producer via a dedicated fund. This regulation principle is hardly innovative: it is the same as that of "contracts for difference” (CfD)[9] from which renewable energies already benefit in Europe. However, our proposal is to extend this regulation system to all low-carbon production methods, in line with Terra Nova’s proposals in previous publications on the subject over the last eight years[10]. The sums recovered in the event that, as in the current situation, market prices are above the ceiling could be used in two main ways:

- To protect consumers in the context of a substantially redesigned tariff shield, that reflects the overall costs of the system and targets households that need it most, unlike the current generalized, very costly and ultimately not very effective system from a budgetary point of view.

- To enable the funding of the « floor » aspect of the scheme, i.e. the income paid to producers when market prices are below the minimum level necessary to cover the investments made.

In addition to this regulation by CfD mechanisms, long-term contracts (PPAs) should be encouraged to invite suppliers to hedge with long-term production and thus no longer deliberately expose themselves to the volatility of the short-term markets, thereby exposing their customers. Prudent investment rules could thus be applied to the retail market for suppliers to encourage these approaches and stimulate the market outside of public investment. Overall, it is clearly time to admit at the European level that the wholesale market works for short-term optimisation of the electricity system, but that it does not give the necessary investment signals to reach the objectives set by the European Union itself (notably in terms of renewable production or security of supply). The European electricity market directives should also encourage the development of flexibility to enable supply security during peak electricity demand and periods of low production (such as windless periods). To this end, various so-called « capacity » or « strategic reserve » mechanisms have been developed in the Member States to remunerate guaranteed capacity. However, they are very disparate and have mostly been designed at national level, without sufficient European coordination. Targets could be set for Member States in this respect, in addition to the targets for the development of decarbonized electricity production.

We therefore propose two families of measures for the wholesale and retail markets in order to restore an appetite for long-term investment and enable as much decoupling as possible of electricity consumers’ exposure to the price of gas, and generally to excessive volatility:

Proposition 1: For wholesale markets

Introduce a reform that reconciles investment planning with short-term optimisation of the electricity system. To do this, extend the current system of contracts for difference for renewables to all existing and future low-carbon production (subject to CO2 emission criteria), which would have multiple advantages:

- The determination of a remuneration and a price corridor adapted to each technology to allow it to cover its costs in a sustainable way while capturing excess profits[11].

- The ability to use the financial windfalls thus generated by Contracts for Difference (CfD) and price corridors in periods of high prices in a more targeted way to protect consumers and reinvest in a decarbonized energy system.

- The sharing of the rents and risks between producers and consumers (through the intermediary of the state or a third party such as the power transmission system operator) for price stability.

- The extension of the visibility of wholesale markets beyond three years to enable long-term hedging.

This proposal would give operators the visibility they need to carry out investments, with competition at the right level, i.e. when planning and awarding these contracts for difference. It is also compatible with long-term contracts (PPAs) that would be freely concluded directly, by mutual agreement, between an electricity consumer (one or more companies, for example) and a power generation project developer, without intermediation by the State.

This reform would lead to explicit public planning of investments (by the State, the power transmission system operators, or both), which is in fact already the case with European and national targets for renewables, coordination between network operators to ensure balance, standardized reserve sharing rules, reserve obligation to stabilize the frequency of the electricity network, etc. This planning would moreover be compatible with market operation, where certain operators could make investments in assets on their own initiative in order to be better covered in the long term. However, such a reform should not be carried out at the expense of European coordination and solidarity, but rather on the basis of various integrated planning levels. Therefore, we also propose to:

- Strengthen coordination at European level[12] of national planning in terms of electricity production.

- Set European supply security targets allowing the remuneration of means of decarbonized flexibility in a harmonized framework

Proposition 2: For retail markets

At the same time, it will in any event be necessary to strengthen the regulation of the retail market by introducing a system of prudent investment rules for electricity suppliers. The latter have similarities to banks in that they provide a service that is essential to consumers and the functioning of the economy, and they are exposed to potentially large variations in wholesale market prices, which are themselves strongly coupled to imported fossil gas prices. It is therefore necessary to ensure their viability, by obliging them to respect a certain number of financial soundness criteria (available cash, solvency, long-term contracts or production assets enabling them to meet the needs of their customers, etc.) before authorizing them to operate, and to prohibit abusive practices (abandonment of customers, etc.). This new regulation could be based on various principles:

- Regular monitoring of suppliers’ coverage rates in relation to their portfolios by national regulators, to be assessed on the basis of their available assets. These hedges with suppliers could be ensured by long-term contracts, sufficient dedicated cash flow, and their own production facilities, etc. As with banks, regular stress tests could be carried out to assess the capacity of suppliers to withstand a sudden change in market prices and avoid the cascading defaults that we have seen this year. The stakes are high: if too many suppliers are unable to withstand the stress tests or gradually abandon their customers, it is generally either the incumbent operator who is responsible for supplying the abandoned customers at its own expense, or the customers themselves who are left to face a market that they do not control, with a supplier to be found in a hurry (and whose price proposal is generally not favourable to the consumer, which can then lead to an increase in energy insecurity or a loss of competitiveness for businesses). The challenge is all the more significant given that suppliers’ many customers include local authorities and public services that must be able to ensure the continuity of their services without being exposed to disruptions due to the sudden rise in energy bills. Progressive sanctions or even withdrawal of supply licences could be envisaged for non-compliance with hedging standards.

- The reform of the supplier of last resort system, the financing of which should be shared between all suppliers like an insurance policy, because that is effectively what it is.

- Relaxation of the rules on long-term contracts for direct consumers (in particular allowing high-consumption customers, the so-called top of the portfolio, to commit themselves beyond three years) or groupings of suppliers to supply end customers. These long-term contracts, together with the above-mentioned prudent investment rules limiting speculation, should allow consumers to benefit from these long-term prices rather than being exposed to the vagaries of the market.

These three points would ensure that suppliers always had the means to supply their customers, including through long-term contracts concluded with (CfD) or without (PPA) state mediation, while being able to trade hedges on dedicated markets and cover themselves on the retail market with customers committed to the longer term

Contrary to the shortcuts and sometimes misleading statements that have been made in the public debate in recent months, there is no miracle formula for decoupling gas and electricity prices. However, it is possible to give electricity consumers significant protection against the repercussions of a surge in gas prices with appropriate regulation of electricity production facilities that encourage long-term investment and allow the capture of excess profits. This may be accompanied by appropriate regulation of the retail market to ensure that players are covered in the long term and that consumers benefit from this. The proposed new regulation would thus make it possible to invest in decarbonized means of production, via long-term contracts whose prices could be integrated into the retail price and thereby avoid too strong a coupling of prices to a balancing price often determined by fossil gas prices. This decoupling of gas prices from electricity prices would thus be gradual, as new investments are made and the retail market is able to integrate long-term contracts.

Energy markets are an opportunity for the European Union, its industries and its consumers. In particular, they represent a competitive differentiator compared to the United States, whose electricity systems are largely disconnected, less resilient and, from this point of view, less economically efficient.

The current situation, however, calls for a review and reform of these markets in order to return to goals of local, low-carbon, competitive production. The construction of the European electricity market dates back to a time when electricity systems were largely characterized by overcapacity and energy transition remained relatively low on the political agenda. We have now entered a period where it is a priority and requires long-term investment. Generalized regulation through Contracts for Difference (CfD), more flexible access to long-term supply contracts (PPAs) with management of commitment periods, increased European coordination and consumer protection are the key tools to face the crisis by restoring an appetite for long-term investment. In the long term, it would make it possible to protect consumers against variations in the balancing price, which is currently strongly coupled to the price of gas, via this system of long-term contracts for new capacities to be developed. However, it would require acknowledging past failures without destroying that which brings cooperation beyond national interests, economies of scale, security of supply and resilience.

[1] This objective of passing on short-term prices has reached an extreme with the obligation for suppliers to propose “at cost” offers, i.e. a dynamic price reflecting the market price at any given time, thus completely exposing the end customer to market variations. Unsurprisingly, all the suppliers who anticipated this regulatory change by offering such a service have withdrawn from the retail market.

[2] This left any customers who could not benefit from a regulated tariff without a supplier, and having to find offers urgently at very high prices. This is the case for businesses as well as for public services in Member States

[3] To give just a few examples from the authors’ previous publications: « L’économie de marché ne suffit pas à financer nos besoins en infrastructures électriques » (“The market economy is not sufficient to finance future electricity infrastructure requirements”) (Nicolas Goldberg, L’Usine Nouvelle, 2016; « Nouveaux enjeux pour les marchés de gros de l’électricité » (“New challenges for wholesale electricity markets”) Antoine Guillou, Christophe Schramm, Esther Jourdan, Jeannou Durtol, Pierre Musseau, Terra Nova, 2014

[4] The Exeltium contract is an electricity supply contract through which certain consumers can purchase their electricity for 30 years, thus providing long-term price visibility for both the producer and the consumer.

[5] Such as support mechanisms for renewables and supply security, made necessary by the lack of relevant investment signals.

[6] This does not mean alignment: States may continue to make different choices, particularly in terms of whether or not to use certain types of energy, but they must share their production and consumption reduction objectives with their neighbours in a transparent manner.

[7] Contracts for Difference (CfD) are contracts between the state and production facilities that provide a fixed remuneration guaranteed by the state for several years. With this type of contract, the producer sells its production on the wholesale market at the market price and the State supplements the price difference if the market does not allow it to reach the remuneration set in its contract with the State. When markets are higher than the remuneration set in the CfD contract, the producer sells on the market and pays back the profit above the set remuneration to the state. This system, which is widely used in Europe, enables electricity production facilities to earn a decent return while avoiding “excess profits” when market prices are high.

[8] Source: REE website, https: //www.ree.es/en/datos/generation/generation-structure

[9] As explained above, Contracts For Difference (CfD) amount to a price corridor where the income cap and floor would be set at the same level. The operator thus has a fixed income regardless of the market price, ensuring that it can cover its costs while paying back its surplus profit to the state when the market price is above its contract price.

[10] “Pour un débat serein sur la Programmation Pluriannuelle de l’Energie: une stratégie claire pour le secteur électrique" (« For a calm debate on the Multiannual Energy Programme »), Antoine Guillou and Nicolas Goldberg, Terra Nova, 2018

“Nouveaux enjeux pour les marchés de gros de l’électricité” (“New challenges for wholesale electricity markets”) Antoine Guillou, Christophe Schramm, Esther Jourdan, Jeannou Durtol, Pierre Musseau, Terra Nova, 2014

[11] This regulation is justified on the basis that an asset should not generate excess profits, if in return a guarantee is provided that it can cover its costs. The alternative to this system of regulation, which we believe is ideal for regulating an existing asset with a good balance between covering its costs and protecting consumers, could be long-term contracts with rules on supervision, transparency of clauses and prices so as not to create too great a disparity in downstream tariffs.

[12] This does not mean alignment: States may continue to make different choices, particularly in terms of whether or not to use certain types of energy, but they must share their production and consumption reduction objectives with their neighbours in a transparent manner.